Love at the End

Corita Kent, Art Workers Coalition, Karolyn Hatton, Sophy Naess, & Portal Publications

a digital exhibition

May 1st - June 15th, 2021

Individual Artworks

Install Views

Press Release

When Americans challenge existing orthodoxies new voices emerge. In order to inspire impactful change, the artwork that rises from these conflicts must visualize and offer both an alternative future and an alternative system of commerce. The exhibition Love at the End explores how the visual culture of dissent and this voice has evolved over the last sixty years. Protests have evolved from the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam war through the Arab Spring, the various Occupy movements, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests and today’s powerful Black Lives Matter movement. But many of the calls for change remain the same; a stop to systemic racism, police/military violence and an increased questioning of capitalist systems.

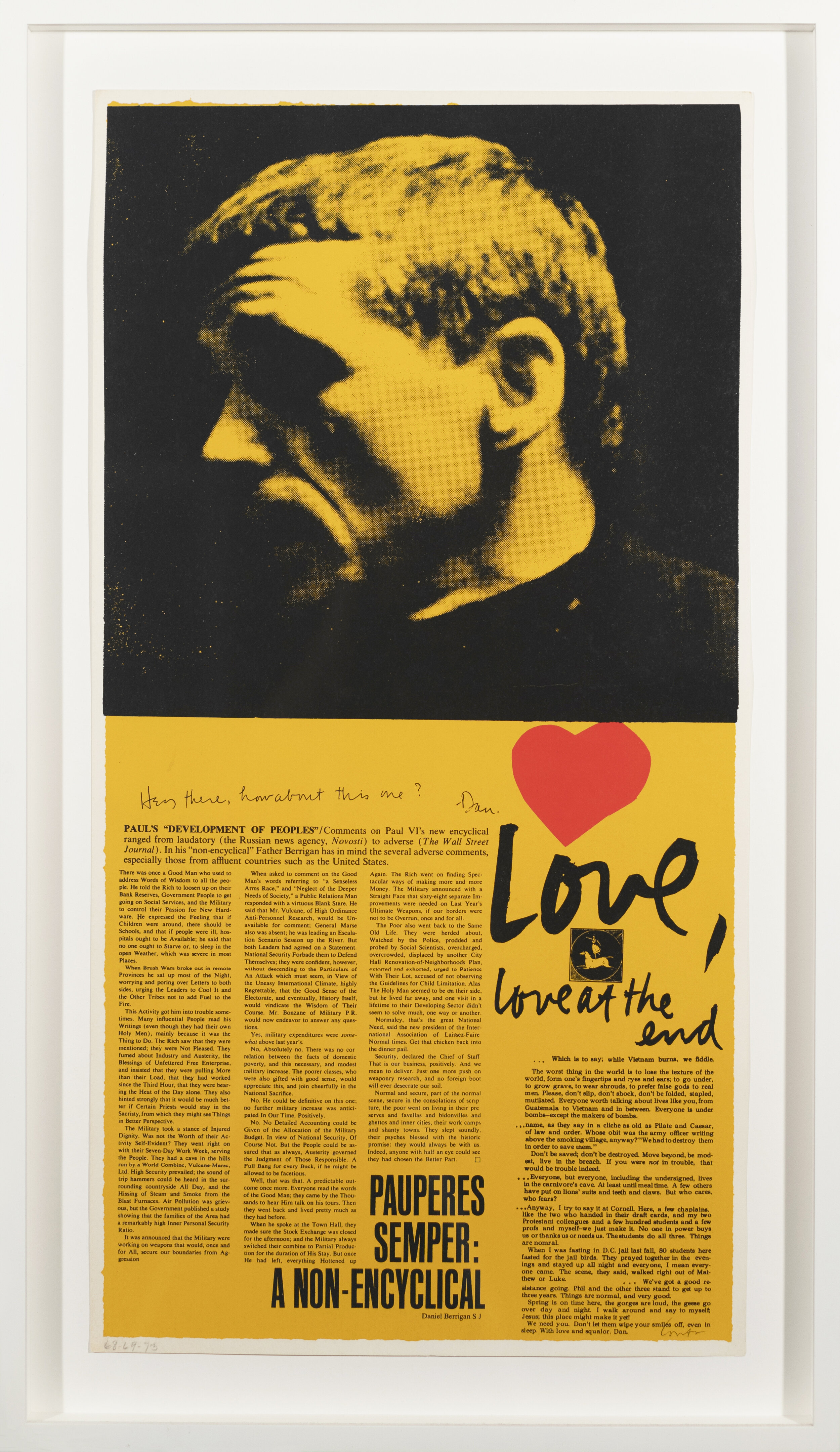

At the age of 18, Frances Elizabeth Kent entered the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and officially took the name Sister Mary Corita (aka Corita Kent). She went on to teach in and eventually head up the art department at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles where she built a print shop, and a welcoming community, that spoke out against poverty, racism, and war using cheap and publicly available serigraph editions (screenprinted posters). She used an iconic blend of biblical verses, advertising slogans, popular song lyrics, poems and literary quotes to assemble her message and combined them with formal compositions reminiscent of both Matisse’s cut-outs and Warholian pop art of the time. Most importantly, the work as a whole described an alternative way of living in the face of fractured and tumultuous times, one filled with community, faith, love, forgiveness and humanity.

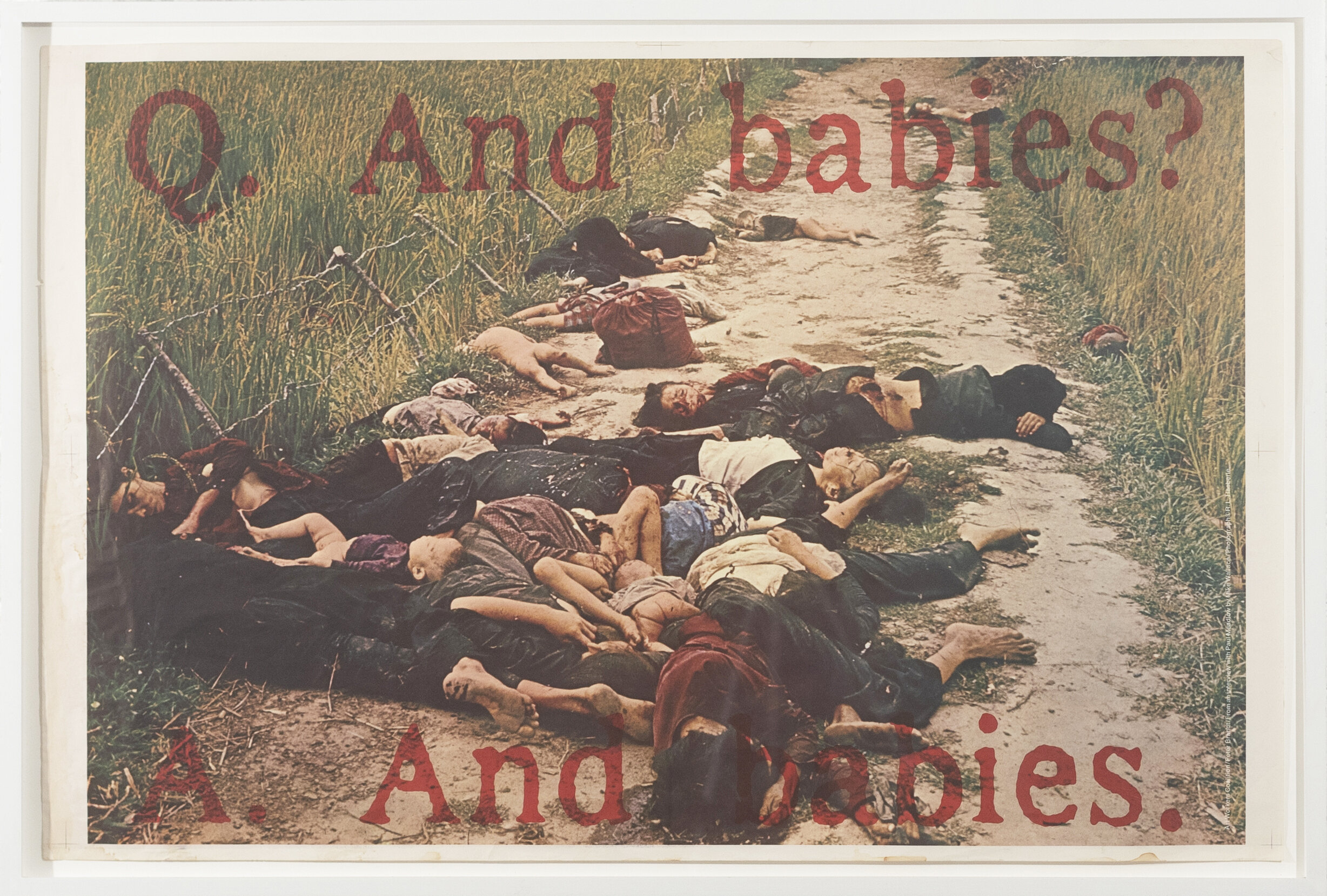

Art Workers' Coalition was a loose coalition of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics and creative workers. The group formed in 1969 as a response to underrepresentation of women/BIPOC in museums and capitalistic priorities in the art world as described in their thirteen demands for reform. After organizing to address MoMA directly, their message broadened to issues including but not limited to racism, sexism, abortion rights, and Vietnam. They directly pressured museums into taking a moral stance on the Vietnam War, an action that resulted in the creation of the My Lai massacre poster “Q. And babies? A. And babies,” 1970. This poster was carried during anti-war demonstrations in front of Pablo Picasso′s Guernica at MoMA in 1970, folding together the gruesome reality of a current war with an artistically rendered version, cleansed and defused. The coalition provided a brief but organized voice championing artist’s rights in both commercial transactions and representation, earnestly asking in a typed piece of ephemera from June 1969 “Should art be free? Can artist be free?”

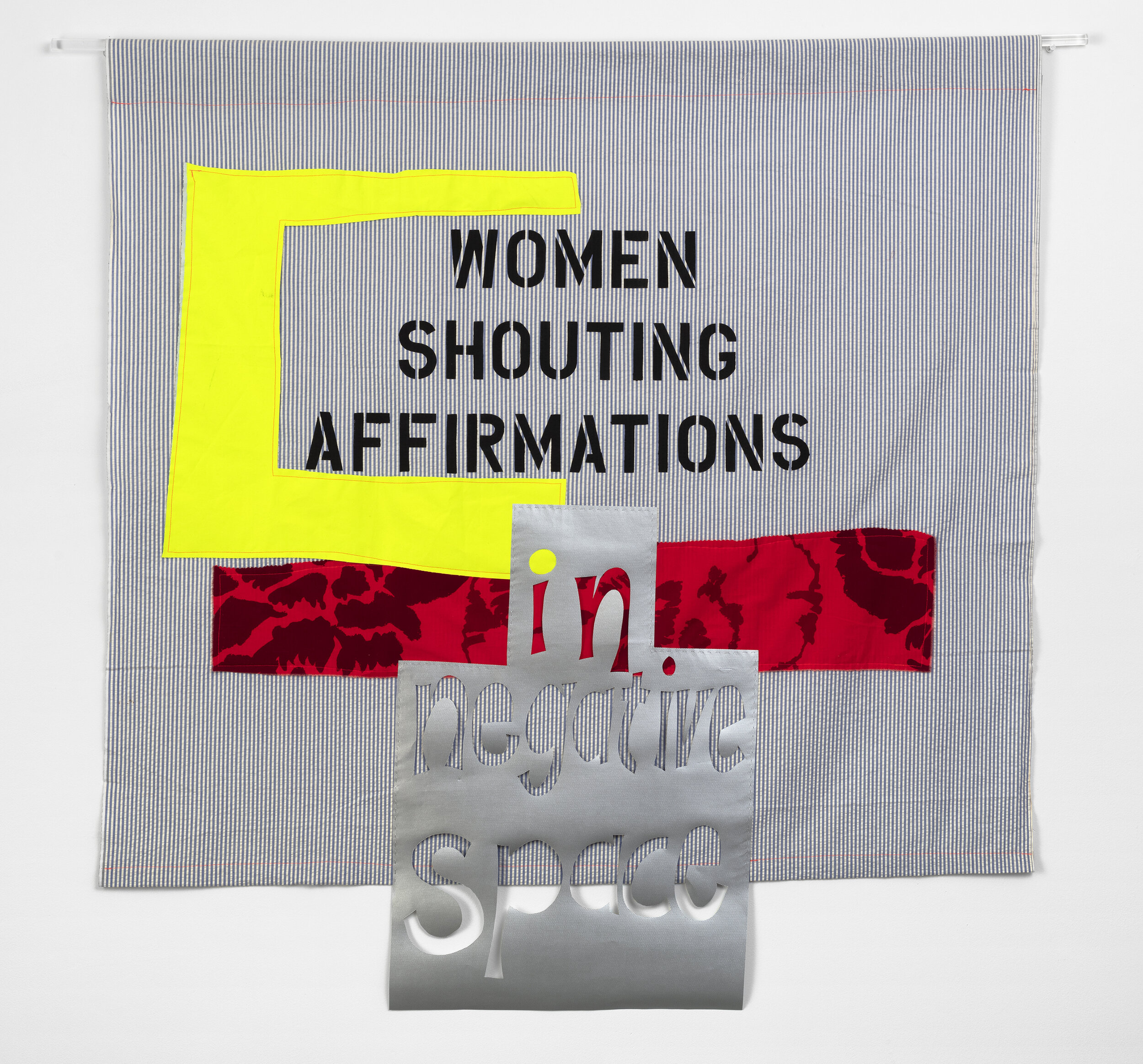

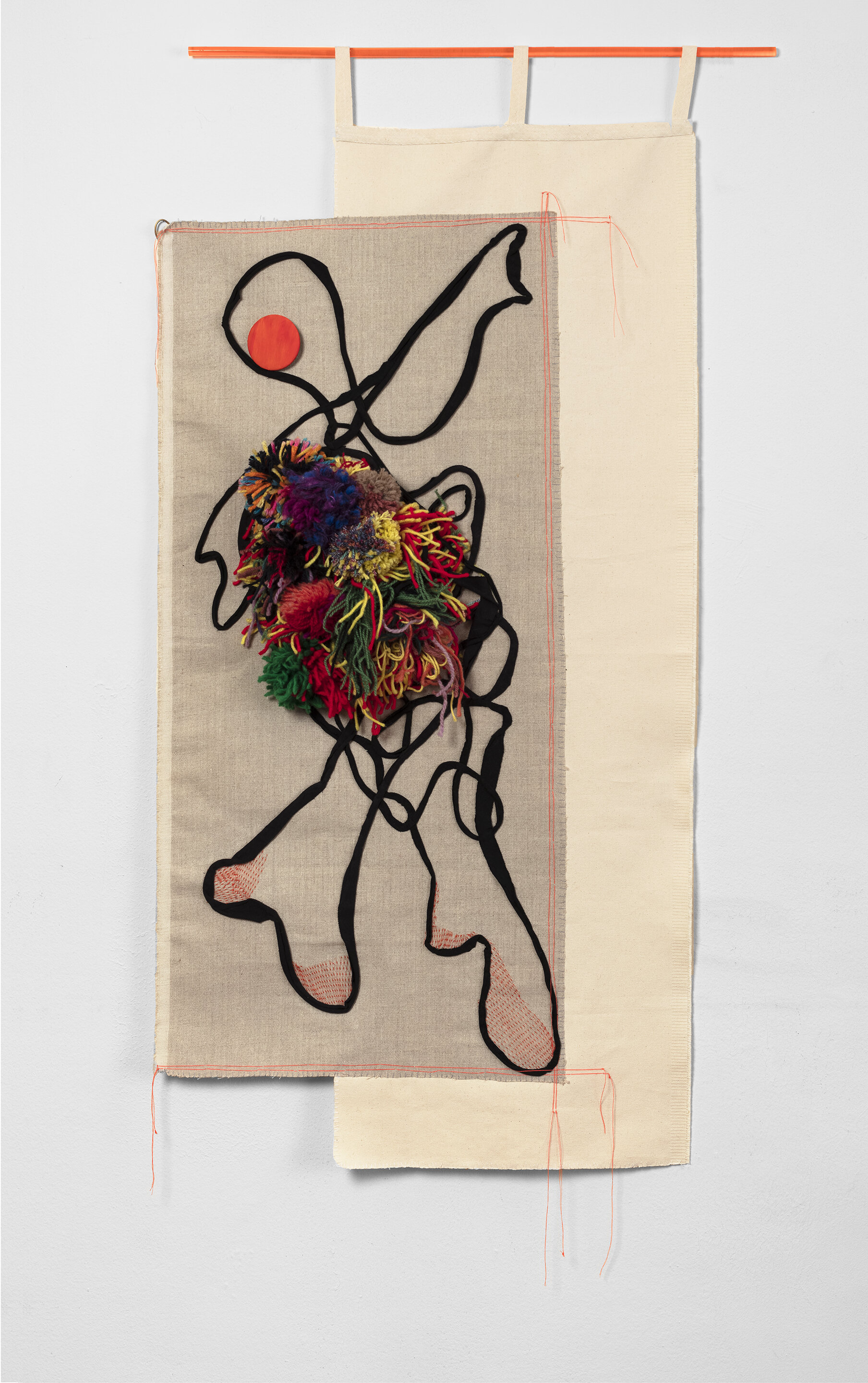

Karolyn Hatton’s banners and wall hangings give a nod to punk ideology, conflict textiles and all-encompassing lifestyle choice to express style and identity outside the boundaries of popular culture. Before upcycling entered the cultural lexicon, artists such as Andrea Zittel and Susan Cianciolo used handmade fashion as an expression against commodification and over-consumption. Wearable statements of dissent span from the suffragettes to the current superhero capes of the Wide Awakes - in some ways Corita’s nun habit could be considered a wearable symbol of protest as well. Hatton’s work shares a space with all of these characters, sharing a formal language and sense of community with Corita. She creates a look book of tenderness, rage and humor.

From 2015 through 2020, Sophy Naess created a subscription service called the Sophy Naess Supporters Circle where members would receive a 22" square hand-printed silk scarf on a monthly basis. A simple and engaging system of reaching people, the subscriptions challenged traditional conventions of art commerce, how art is distributed and how art is consumed. She was able to weave a narrative over time as well, each scarf pointing to her current thoughts and/or current events. Scarf #41 The Squad, 2019 proudly depicts Congresswomen Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib who Trump infamously told to "go back" and try to fix the "crime infested places" they "originally came from" while #32 shows a vivid drawing of the tortoises and the hare fable. When seen together, the scarves become storyboards of a larger narrative, one that describes a strong democratic future entwined with the lessons of nature.

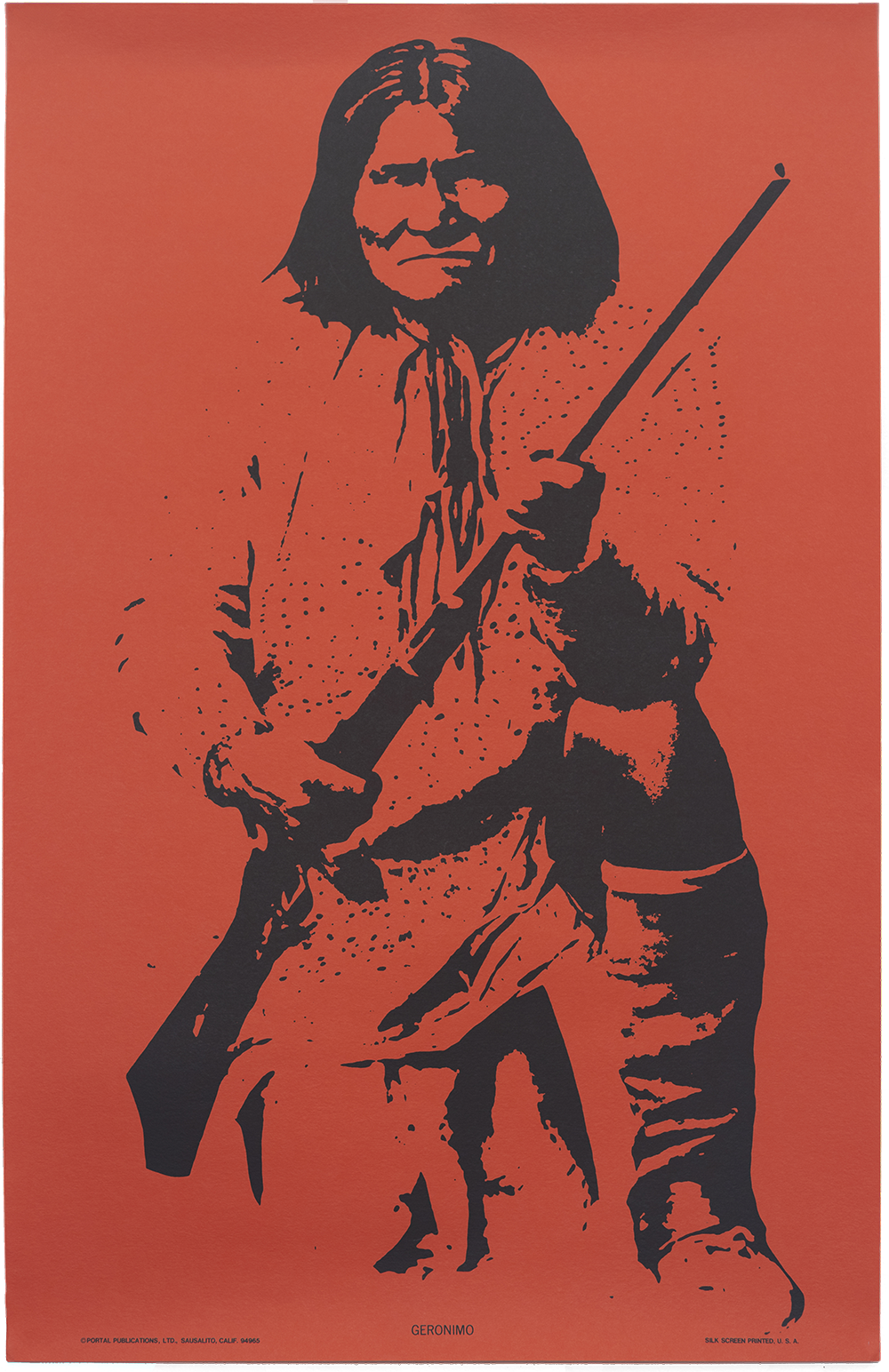

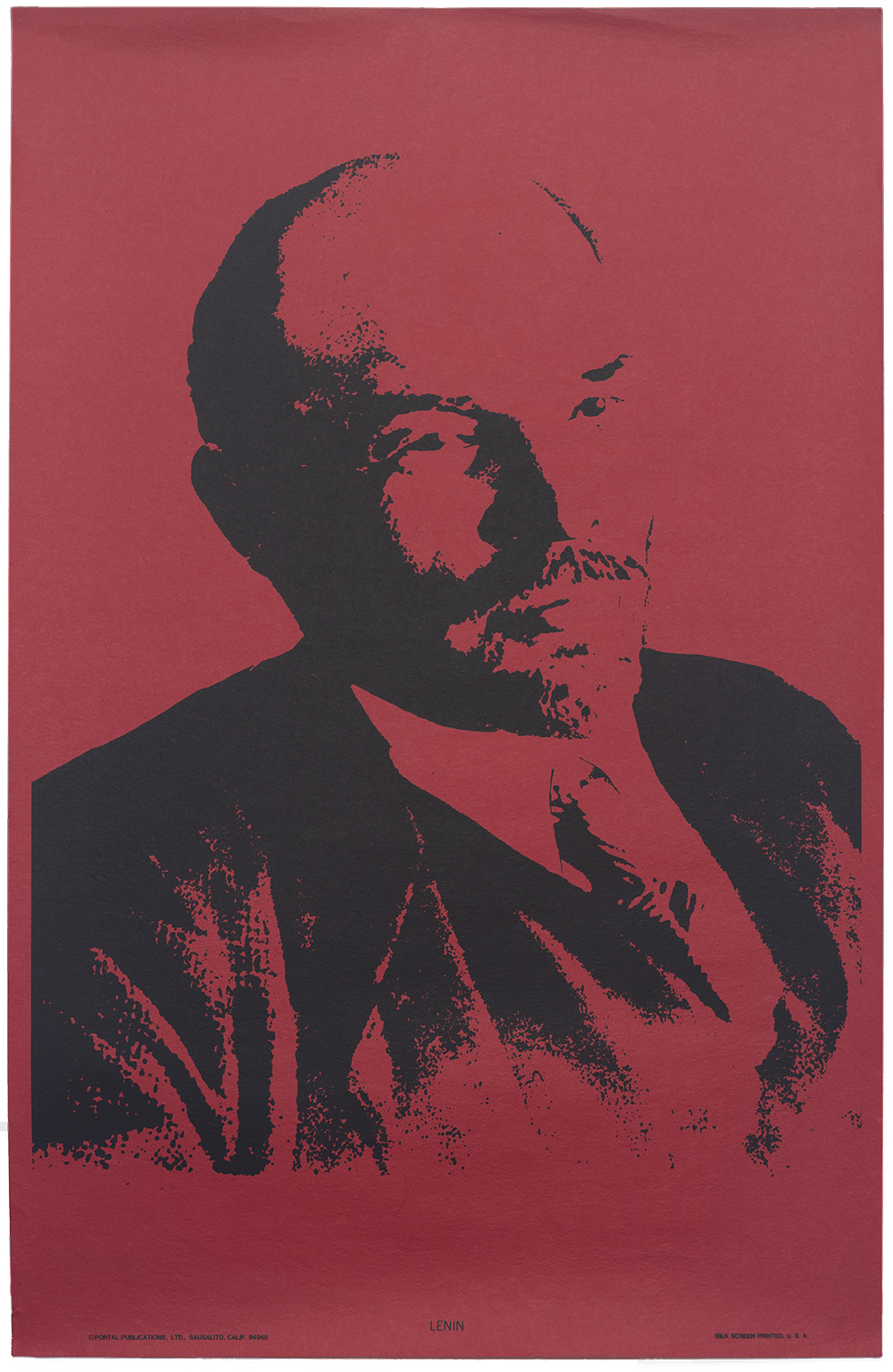

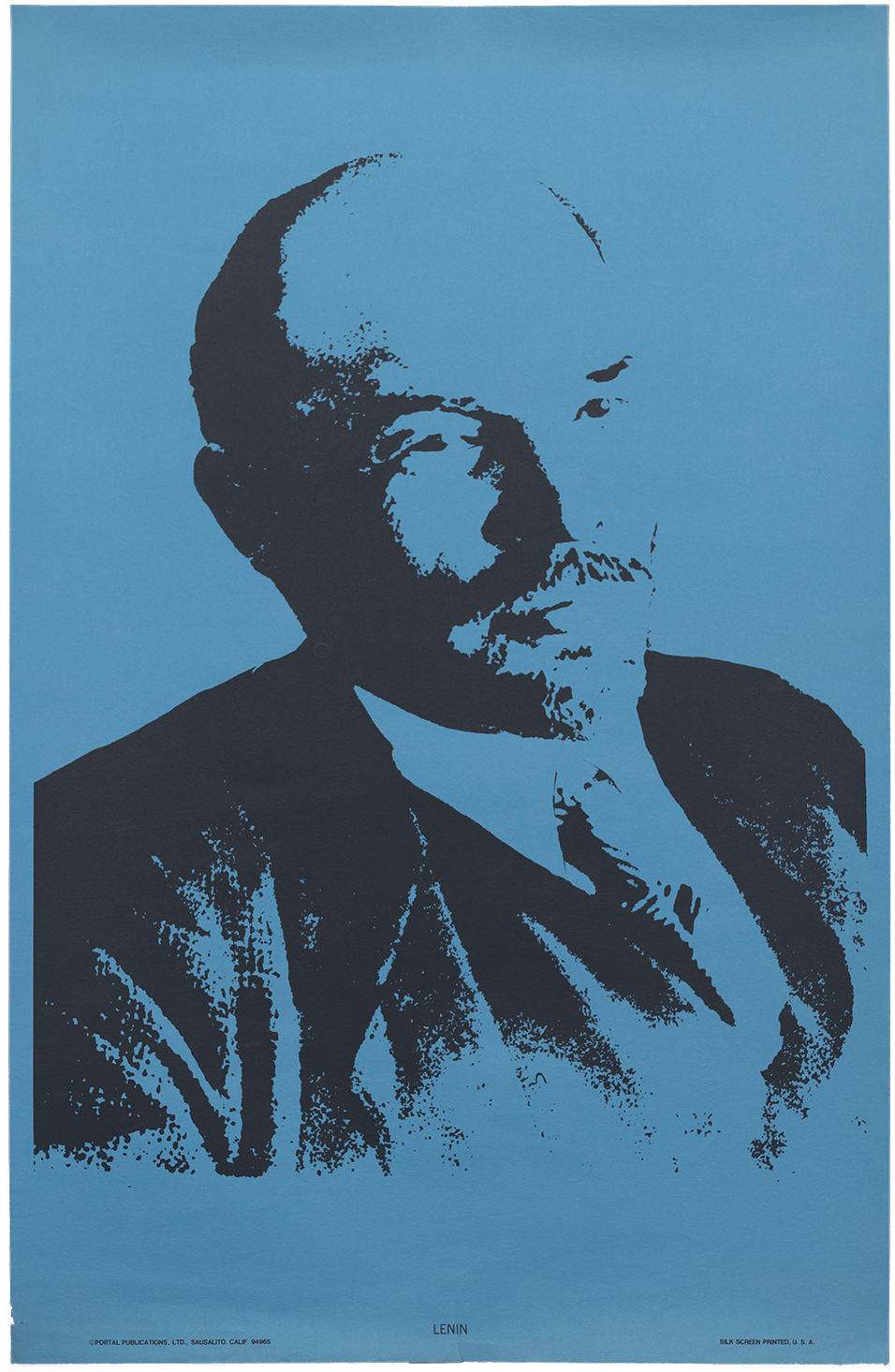

In the 1960s and 70s the San Francisco Bay Area hatched a huge number of small, specialized printing ventures. McCarthyism had previously meant there was very little print produced by ideological and political movements for fear of retaliation but by the early 60s, San Francisco’s music counter culture started producing free posters for concerts, inspiring a boom in leaflets, flyers and most importantly, eye-catching posters. Known as the Bay Area radical print shops, these presses produced visual culture that was both commercially and ideologically free for all. Portal Publishing, a more traditional movie poster company in Sausalito, joined in with a series of graphic portraits of Lenin, Geronimo, Angela Davis, Che Guevara and Emiliano Zapata. Immediately recognizable, they merged into the wealth of visual culture running off the presses at shops including the Black Panther Party press, Chicano Art Center, The Community Asian Art & Media Project (CAAMP), Five Trees Press, Inkworks Press, and Mission Gráfica.

Corita Kent

Sister Mary Corita, ca. 1964. Image courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community.

Corita Kent (1918–1986) was born in 1918 in Fort Dodge, Iowa with the given name Frances Elizabeth Kent. In 1923 her family moved to Hollywood, California and at age 18, she graduated from the Los Angeles Catholic Girls’ High School and entered the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, officially taking Sister Mary Corita as her religious name. After a brief teaching assignment in Canada, Corita returns to the Order in 1947 to join the faculty of the Art Department. Completing her master’s degree in art history from USC in 1951, she adopts silkscreen as her medium of choice.

Considered a proto-pop artist, Corita’s work of the 1960’s tackled poverty, racism, and injustice by appropriating the popular language of advertising and consumerism to communicate messages of love and spiritual hunger. Splashy swaths of bright colors were combined with politicizing text extracted from deeply personal journals. Corita, like many artists of the time, hoped to inspire collective action through open dissemination of these words and images. Buckminster Fuller described his visit to the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary art department as "among the most fundamentally inspiring experiences of my life."

Commissions included the Christmas windows display at IBM and the Vatican Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair, both in New York. Corita often worked in collaboration with students and focused on the Order’s Mary’s Day celebration, a traditional procession that she transformed into an exuberant and colorful expression against world hunger.

In 1968 Corita leaves the Order and moves to Boston to focus more on her art making. Exhaustion, insomnia and depression have been cited as influencing factors for her exit but she continues to take commissions including the Boston Gas Company gas tank design, billboards for Physicians for Social Responsibility and a USPS stamp design. But sadly in 1974 Corita receives the first of many cancer diagnoses, a disease she battles continually until her death on September 18th, 1986. She leaves her unsold works and copyrights to the Immaculate Heart Community who in 1997 forms the Corita Art Center to honor Corita’s legacy.

In her lifetime, a major retrospective of Corita’s work was mounted at the deCordova Museum in Massachusetts in 1980. Subsequent exhibitions include the Portland Art Museum, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Harvard Art Museum and Skidmore’s Tang Museum. Her works appear in the permanent collections of over 40 major museums including the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Boston's Museum of Fine Arts and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.