Kira Dominguez Hultgren: Luz Jiménez

March 17 – April 23, 2022

Artworks

Press Release

Heroes Gallery is pleased to present works by contemporary artist Kira Dominguez Hultgren in conversation with the history of Nahua-Mexican artist, model, Nahuatl-language educator, storyteller and weaver Julia “Luz” Jiménez (1897-1965). By engaging with documentation and artwork about Jiménez’s life and the influence she had on the Mexican Modernist School, Dominguez Hultgren weaves an accumulation of cultural narratives and intertwined identities. How is weaving used to authenticate identity both in Jiménez’s life and in Dominguez Hultgren’s?

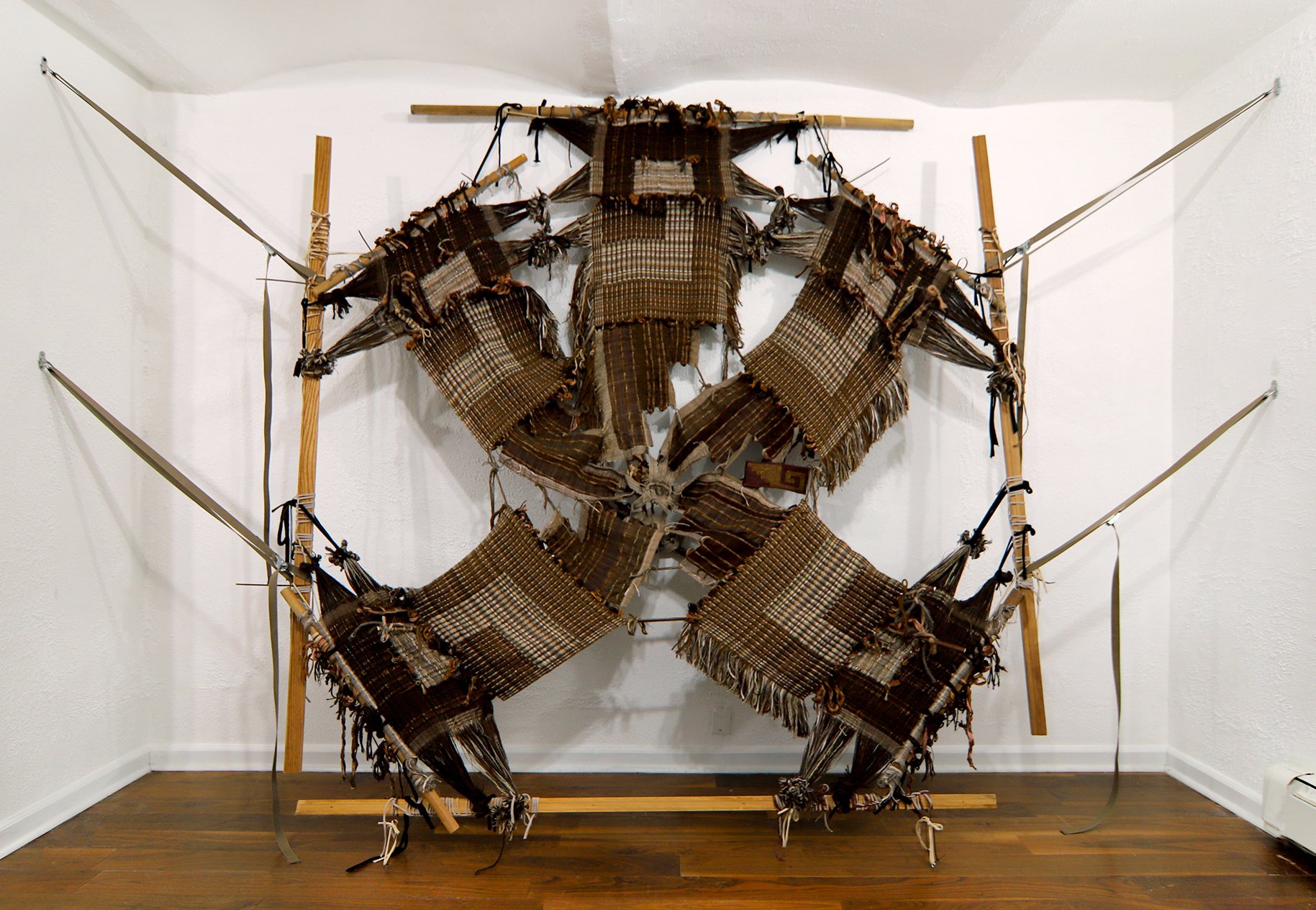

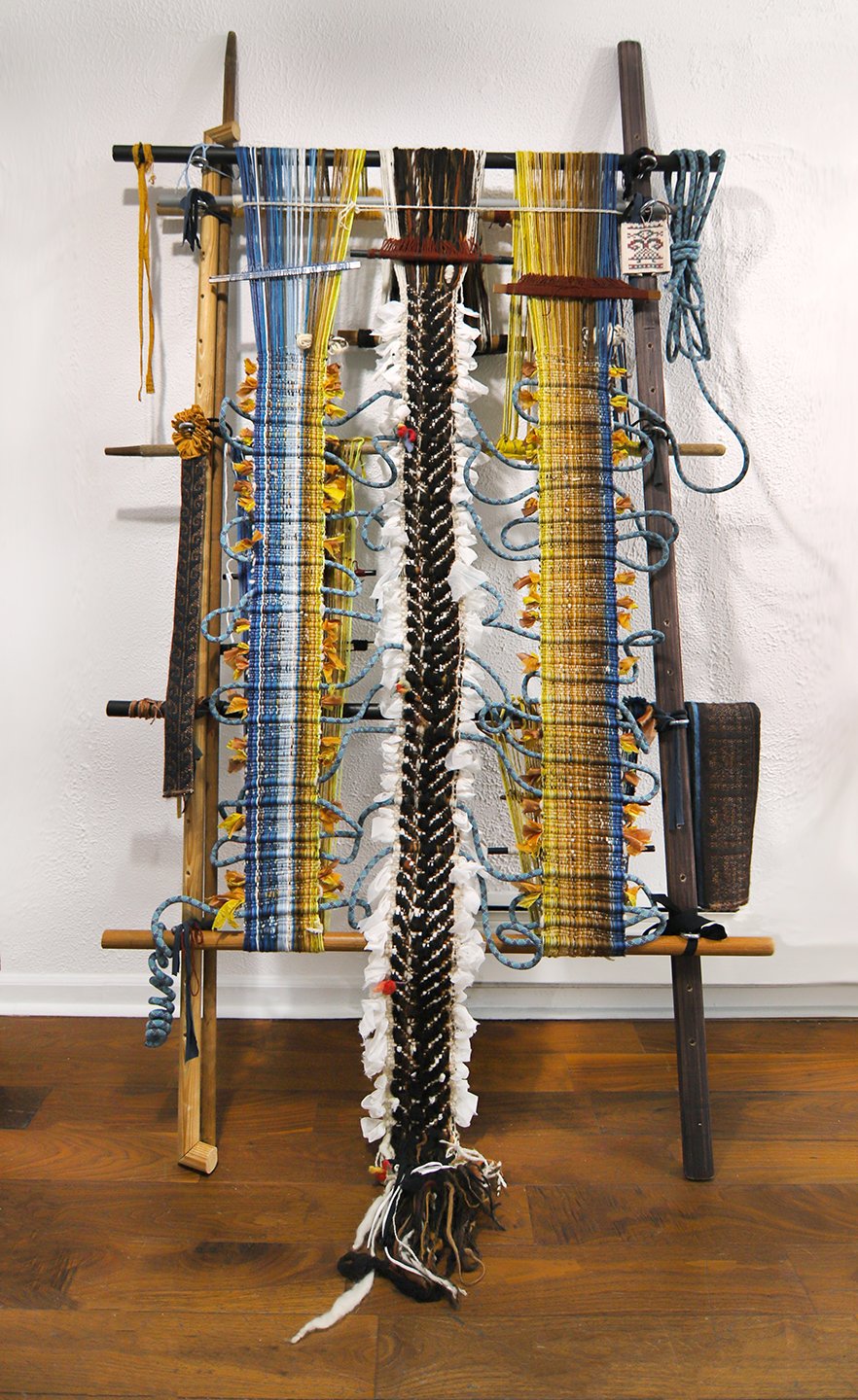

Self-described Chicanx, Indian and Hollywood Hawaiian, Dominguez Hultgren sees her ancestry mirrored in her weaving; an embodiment and performance of strange combinations. She weaves in the tension between performing and preserving cultural identity and finding one’s self within the romanticized ideal of the indigenous woman at her loom.

Dominguez Hultgren states that “in (my) weavings nothing gets blurred; rather the vertical and horizontal materials move in opposite directions, each strand holding its own in-between warp and weft. To weave with competing, unequal materials is to reflect a lived experience of colonialism supported by unequal histories where some stories go unheard, unseen, while others seemingly become the whole story.” Weaving becomes a metaphor in which the intertwining of material represents different truths, personas and perceptions.

What is seen and unseen interlace to create identity. To perform or preserve an identity is not a choice between falsifying and truth-telling, but a strategy to make sense of one’s story in a larger web of non-neutral tensions and histories.

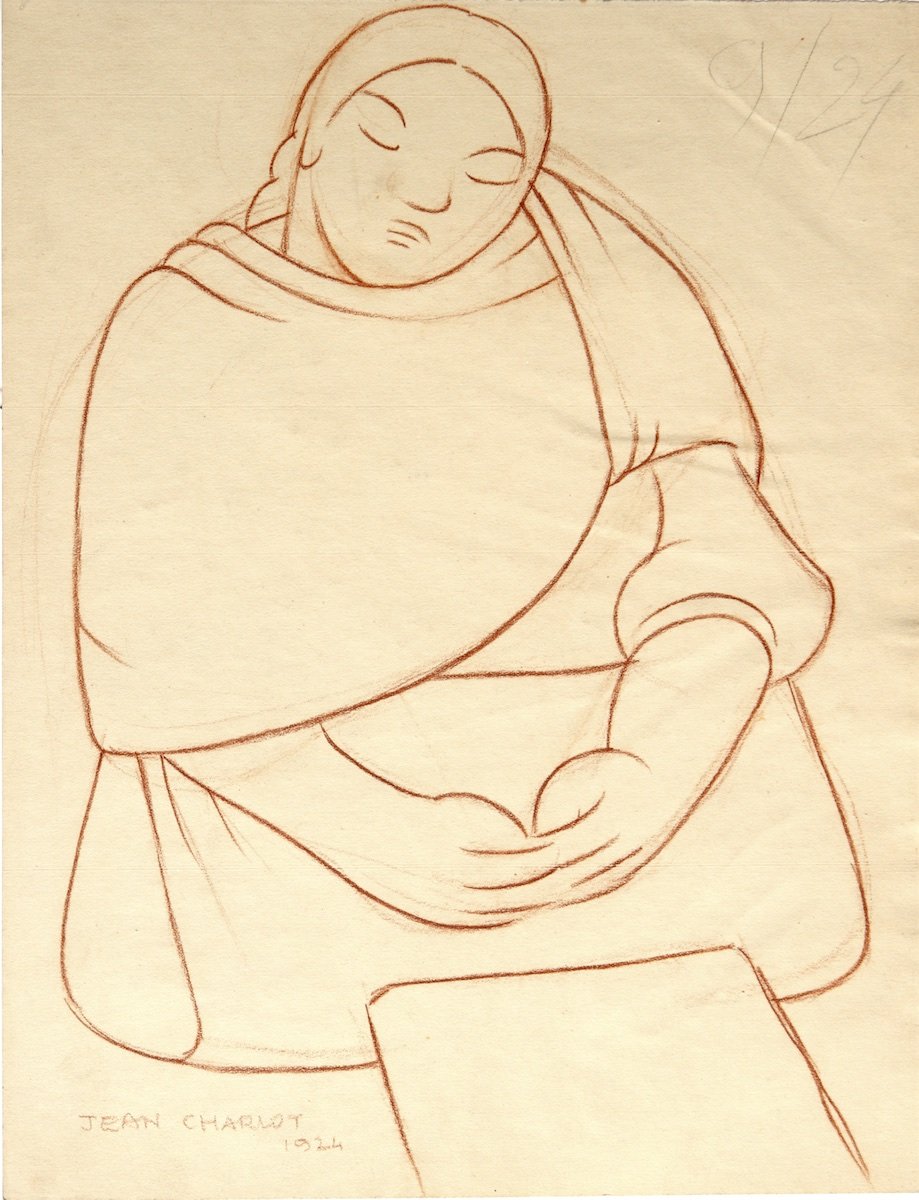

Luz Jiménez lived this tension in her time, using the platforms given to her, using her audience’s perceptions of her, to tie her story and her people to the larger history of the Mexican Revolution and modern art. For members of the Mexican Modernist school such as Diego Rivera, Jean Charlot, Fernando Leal and Tina Modotti, she became a symbol of idealized Mexican identity and the perfect artist-model for their work. Jean Charlot ‘s son and art historian John Charlot explains that for his father, Jiménez was “the woman he saw in all women of Mexico” (Sylvia Orozco, “Luz Jiménez in My World,” 149). Jiménez used this platform to talk about Nahua identity and culture, translate Náhuatl with ethnographers, tell and publish stories of her hometown Milpa Alta before and after the revolution. In other words, Jiménez wasn’t only Mexican; she was also Nahua. She moved though, worked in, and knew the language of many worlds.

Artist and educator Kira Dominguez Hultgren studied French postcolonial theory and literature at Princeton University (2003) and performance and fine arts in Río Negro, Argentina (2012). She additionally holds a dual-degree MFA/MA in Fine Arts and Visual and Critical Studies from California College of the Arts, (2019). She has had solo exhibitions at the San Jose Museum of Quilt and Textile (2020); Gensler, San Francisco, CA (2019) and Eleanor Harwood Gallery in San Francisco (2018 & 2020) and group shows at NADA House, Governors Island, New York City, NY (2021); Minnesota Street Project, San Francisco, CA (2020) and at the de Young Fine Art Museum of San Francisco (2020). Residencies and awards include the Headlands Center for the Arts, Facebook AIR, and Brandford/Elliott Award Nomination for Excellence in Fiber Arts, Textile Society of America. Dominguez Hultgren is currently part-time faculty at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in Fiber and Material Studies and is represented by Eleanor Harwood Gallery in San Francisco.

Luz Jiménez modeling for Ramón Alva de la Canal, Fernando Leal and Francisco Díaz de León at an outdoor painting school in Coyoacán, Mexico, ca. 1920. Image: photographer unknown, courtesy of Fondo Documental y Fotográfico Luz Jiménez and the Fondo Fernando Leal Audirac.

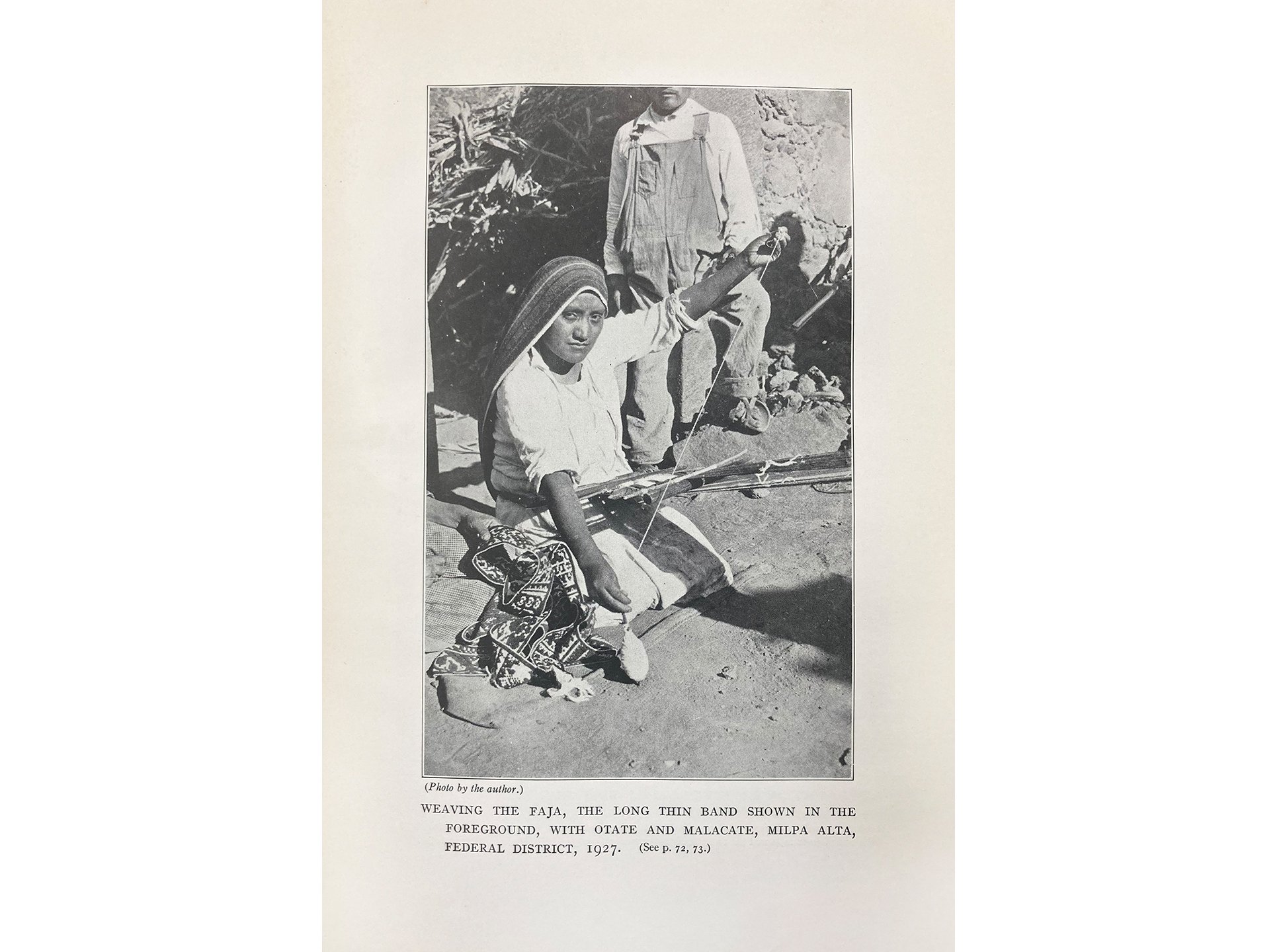

Luz Jiménez (1897–1965) was born Julia Jiménez González in Milpa Alta, just south of Mexico City. A Nahuatl-language storyteller, linguist, weaver and artist model, Jiménez became a muse and educator to the Mexican Muralists eager to add indigenous Nahua authenticity in their politically charged works.

Jiménez witnessed the Mexican Revolution as a young woman. In 1916, Venustiano Carranza’s army massacred her father and all the other men of her village, devastating the remaining family financially and forcing her to move to Mexico City with her mother and sisters. There she worked as a street vendor and in 1919 won an indigenous beauty contest that allowed her to begin modeling at the painting schools that sprung up across Mexico City, their formation a product of the country’s revolutionary violence transitioning into a cultural revolution.

Nahua women and culture came to be seen as a symbol of Mexico’s noble Aztec past and an important part of the national identity following the Mexican Revolution. Romanticized representations of Jiménez wearing traditional indigenous dress began to populate works by Fernando Leal, Jean Charlot, Diego Rivera and other artists in their circle. Although the depictions showed indigenous people in a relatively positive light, they also perpetuated the inaccurate stereotype that “authentic” Nahua people only existed in an idealized, rural landscape; forever frozen in a glorious past. Jiménez’s reality in Mexico City was quite different than the scenes she was painted in, there she often struggled through poverty and relative obscurity within the artistic community.

Jiménez worked closely with Jean Charlot in particular and there are decades of personal correspondence between the two spanning her entire life, even after he relocated to America. He was the godfather of her daughter, Concha and she nannied to his four children over the course of their friendship. In an interview with his son, Jean Charlot spoke of Jiménez’s ability to communicate and educate through their modeling sessions: “There is a whole image there that she projected. Now, many of the other girls could put their village clothes on and pose with a pot on their shoulders, but they didn’t do it, so to speak, to the manner born. And Luz had one thing that was important: She could do it both naturally, as the Indian girl that she was, and know enough so that she could imagine from the outside, so to speak, what the painters or the writers saw in her, and she helped both see things because of that sort of double outlook she could have on herself and her tradition.”

In the 1930s Jiménez worked closely with linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf and anthropologist Robert Barlow to document the Nahuatl language and storytelling tradition. She also collaborated with Anita Brenner and Jean Charlot to create children’s books based on traditional Nahua stories and recounted her life story to Fernando Horcasitas, he later published her testimonials under the title “Life and Death in Milpa Alta: A Nahuatl Chronicle of Diaz and Zapat.”

In 1965, Jiménez was struck by a bus in Mexico City after paying a visit to a friend. Heroes Gallery would like to acknowledge Jiménez’s grandson, Jesús Villanueva Hernández, who works to gather a family archive and dedicates himself to his grandmother’s legacy.