Fin de Siècle

Aubrey Beardsley, Ryan Flores, Trevor Foster, Linda Gallagher & Alan Reid

a digital exhibition

March 1st - April 15th, 2021

Individual Artworks

Install Views

Press Release

The exhibition Fin de Siècle is predicated on the work of 19th century raconteur and aesthete Aubrey Beardsley and his pivotal role and influence in contemporary art. The term “fin de siècle,” French for end of the century, refers to the end of the 19th century (more specifically the decade of 1890s), with its literary and artistic climate of sophistication, world-weariness, and fashionable despair. It is the closing of one era and onset of another; a “between” step in an ongoing cycle. In this exhibition we trace a genealogy of themes through time from Beardsley to four present day artists. The contemporary works in this exhibition orbit and in many ways have evolved from the eight prints by Aubrey Beardsley.

Fin de siècle is widely thought to be a period of degeneracy, symbolism, and decadence; evidence of a society seduced and ensnared by the spiritual, the morbid and the erotic. At the time there was a shared apocalyptic sense of a phase of civilization coming to an end that ultimately defined the time leading up to the first world war. Its cultural hallmarks included ennui, cynicism, egoism, dandyism and mysticism as the philosophical waves of pessimism swept across Europe.

Many of the political cultural themes of fin de siècle have been cited as major influences on the impending fascism of the two world wars. These same themes can be identified again in our current decade of Trumpism and the years leading up to the January 6th insurrection (where cycles diverge and fascism was narrowly averted). With social media spawning a heightened cult of self, navel gazing, decadence, class discrepancy and mystical conspiracy theories it’s important to remember that both times also contain hope for a new beginning, they are on the cusp of a new cycle of heightened equality, freedom and creativity. We are again in a “between” step in the cycle.

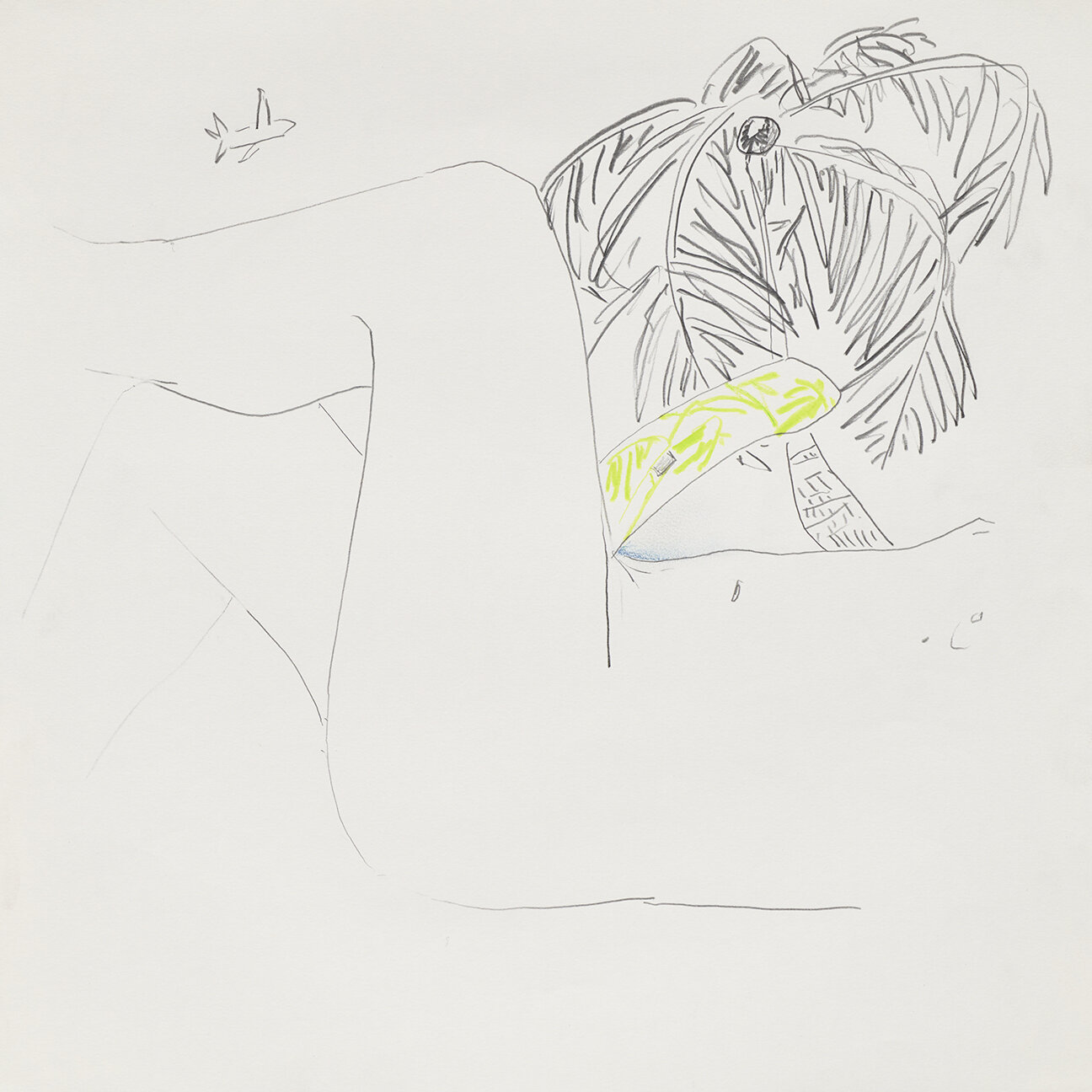

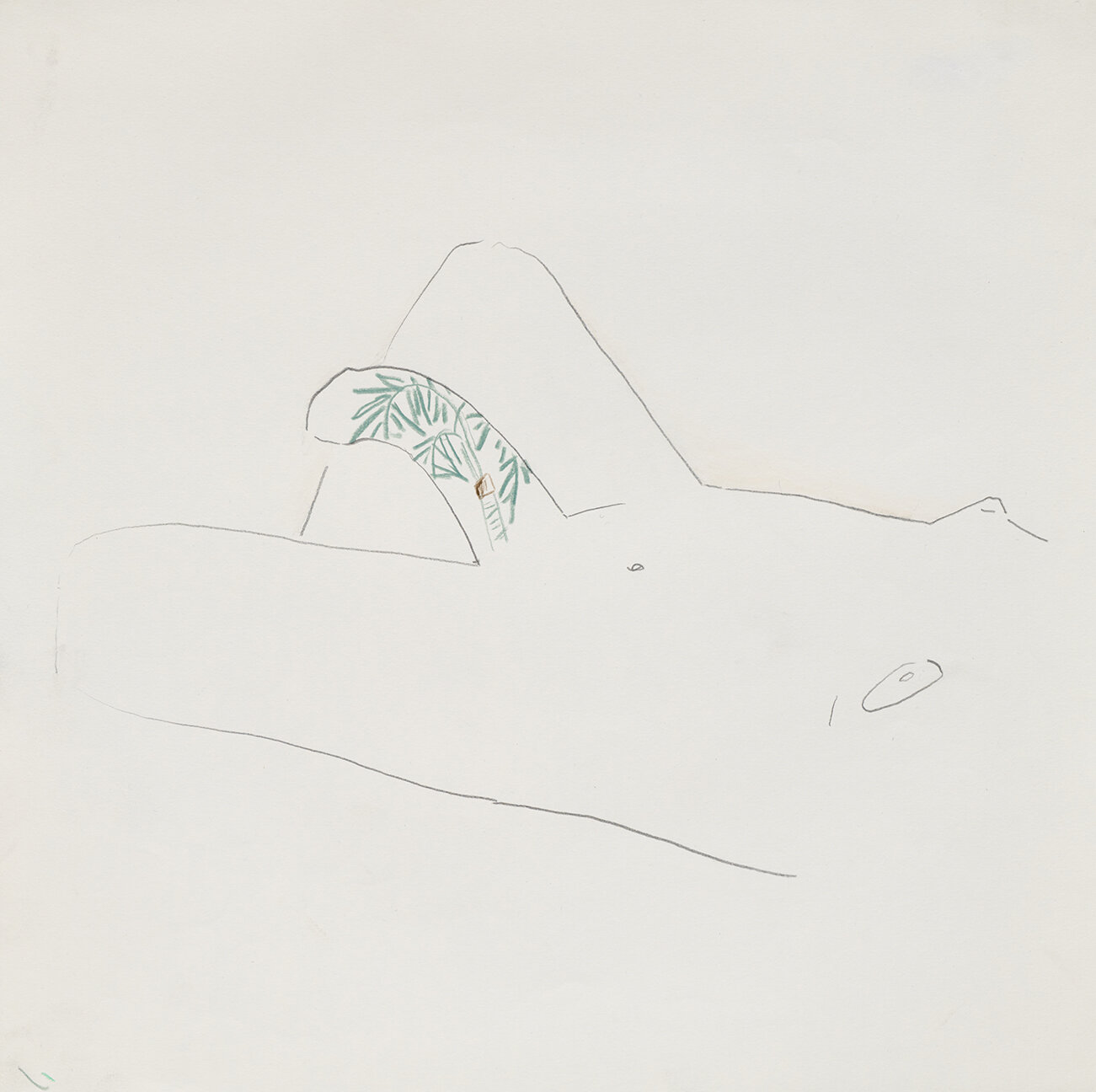

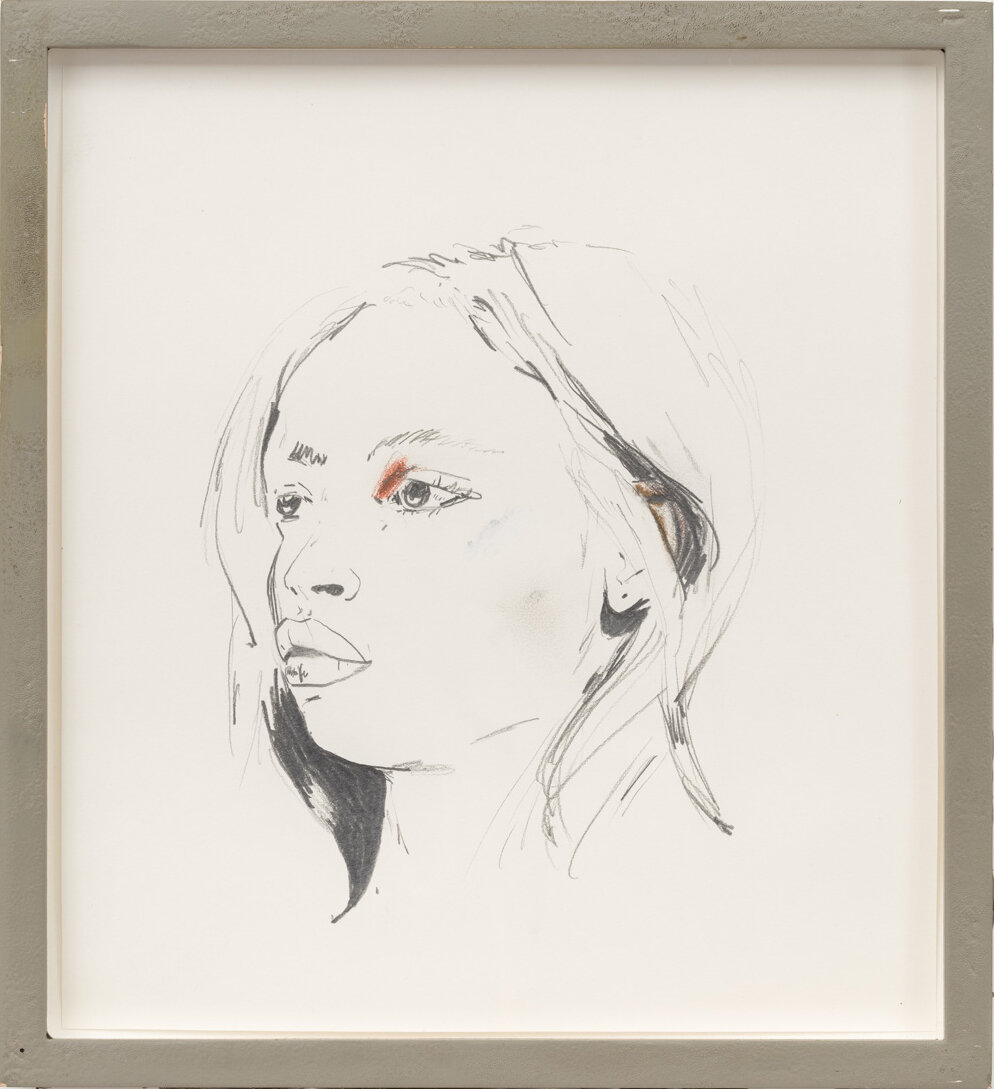

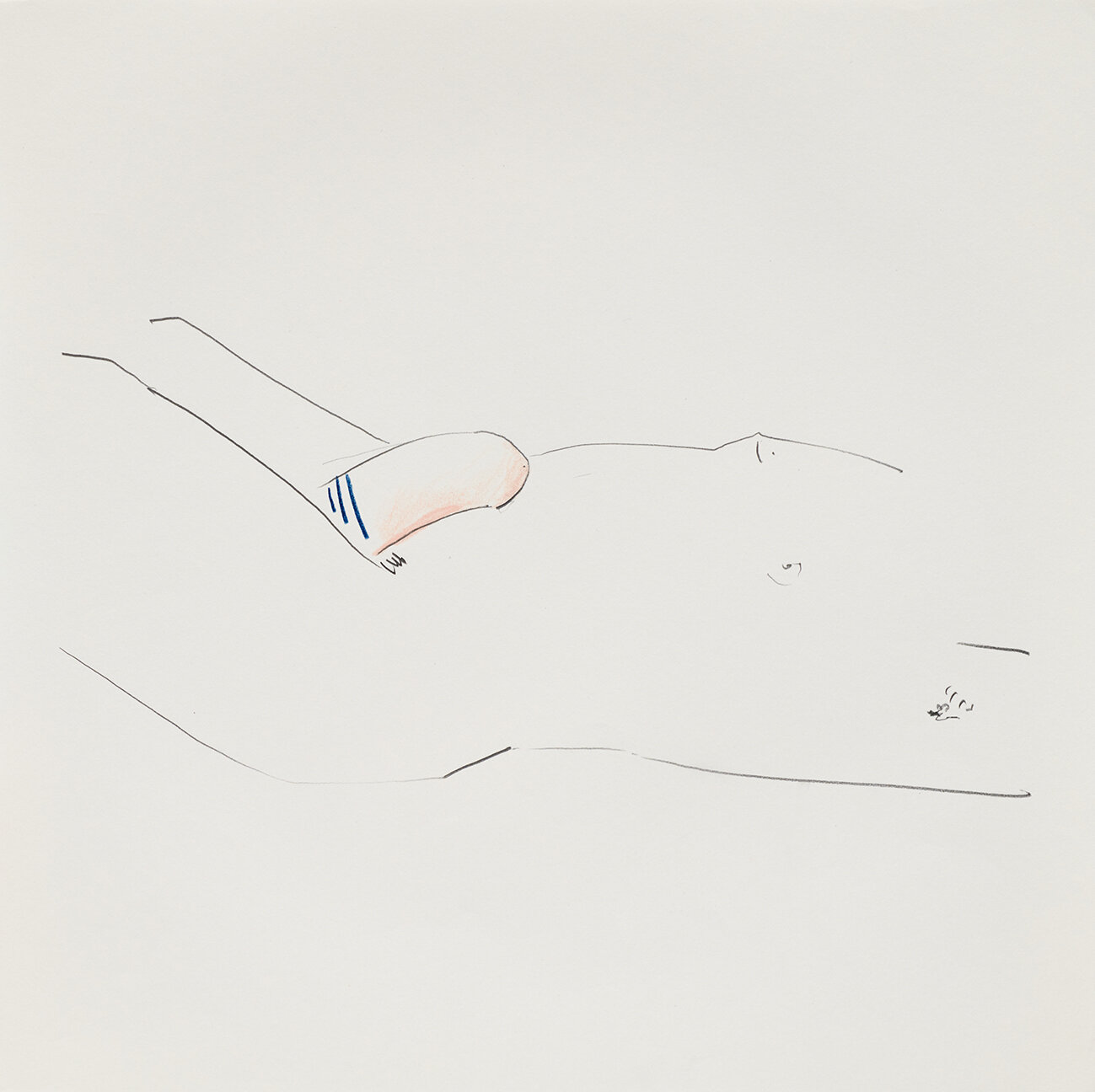

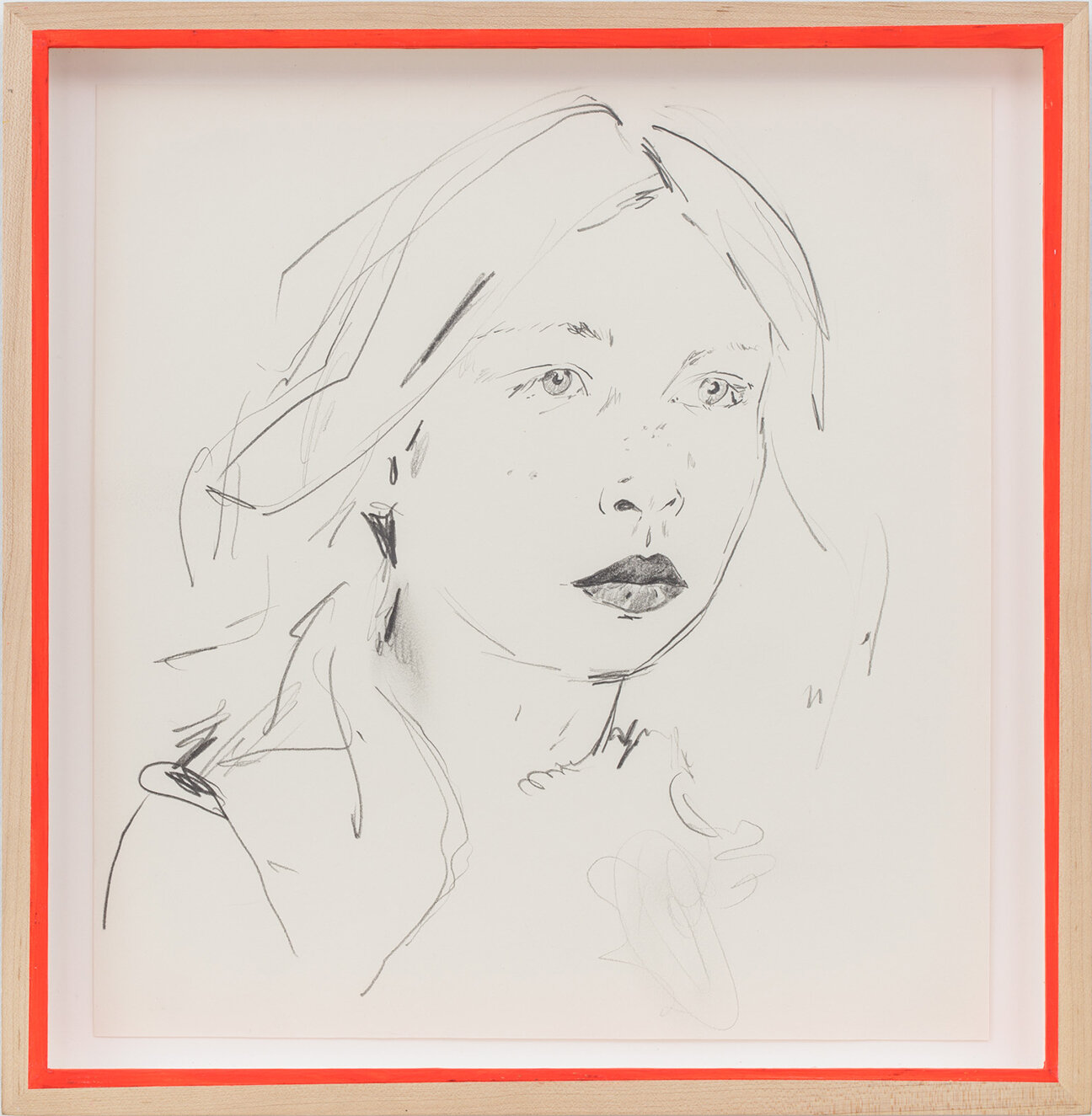

Linda Gallagher’s drawings speak to fin de siècle’s interest in the erotic, the self-referential and sexual longing with an explicit and bold humor. Her three portraits of fashion models show the artifice of beauty for sale but unlike dandyism’s excessive refinement, they stare back with wild and tussled personas. With their smudged lines the heroines are drawn emerging trampled but triumphant from an ordeal with bee-stung lips. Her three male nudes depict dandy-esque pastime of leisurely hobbies; prone and sleepy soft male bodies lying on a beach with palms, plants and tasteful decoration drawn (or possibly tattooed?) on their penises. Beardsley’s obsession with the erotic played upon Victorian taboos much as Gallagher’s plays with modern attraction and allure, aiming to be both provocative and invitingly indecent.

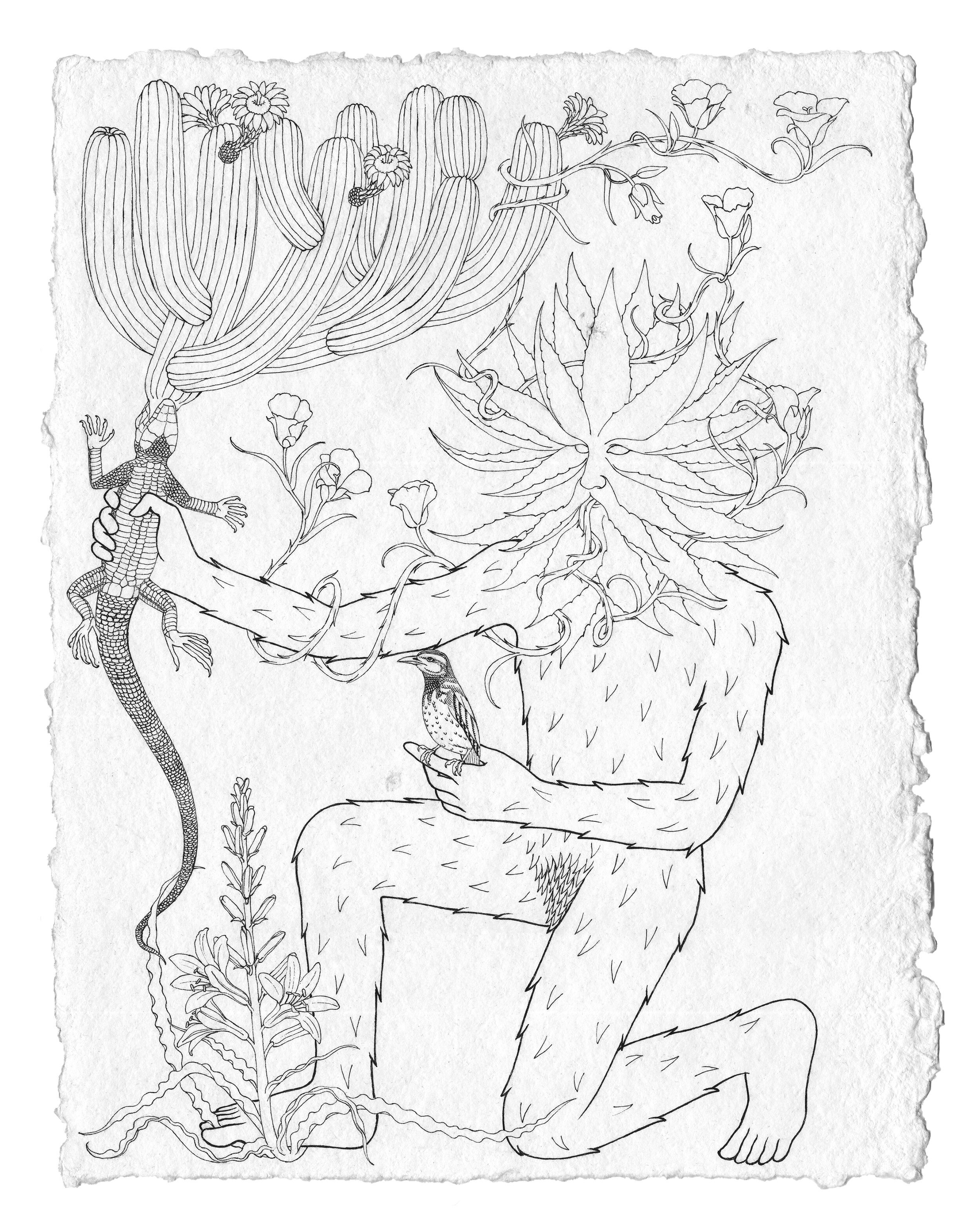

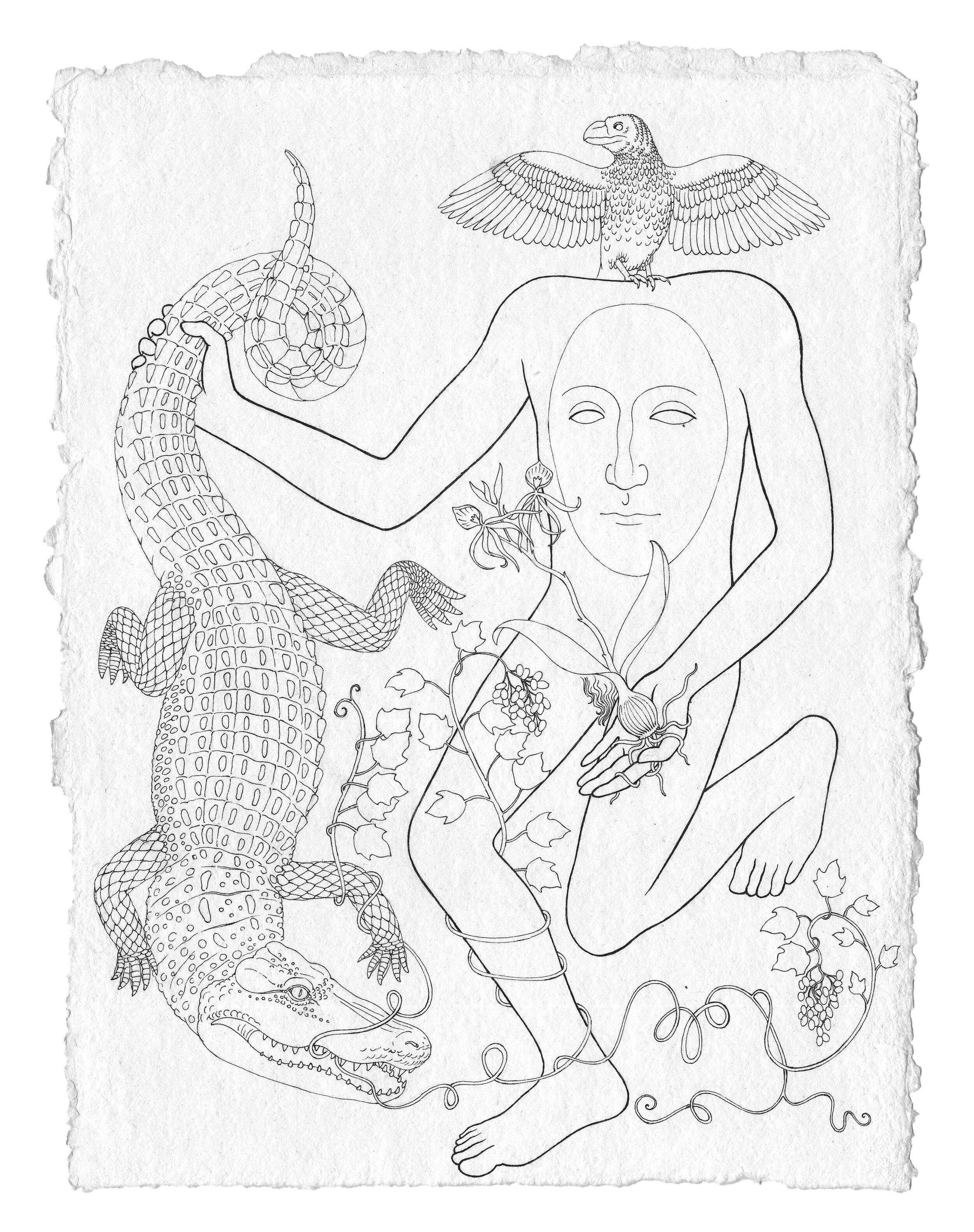

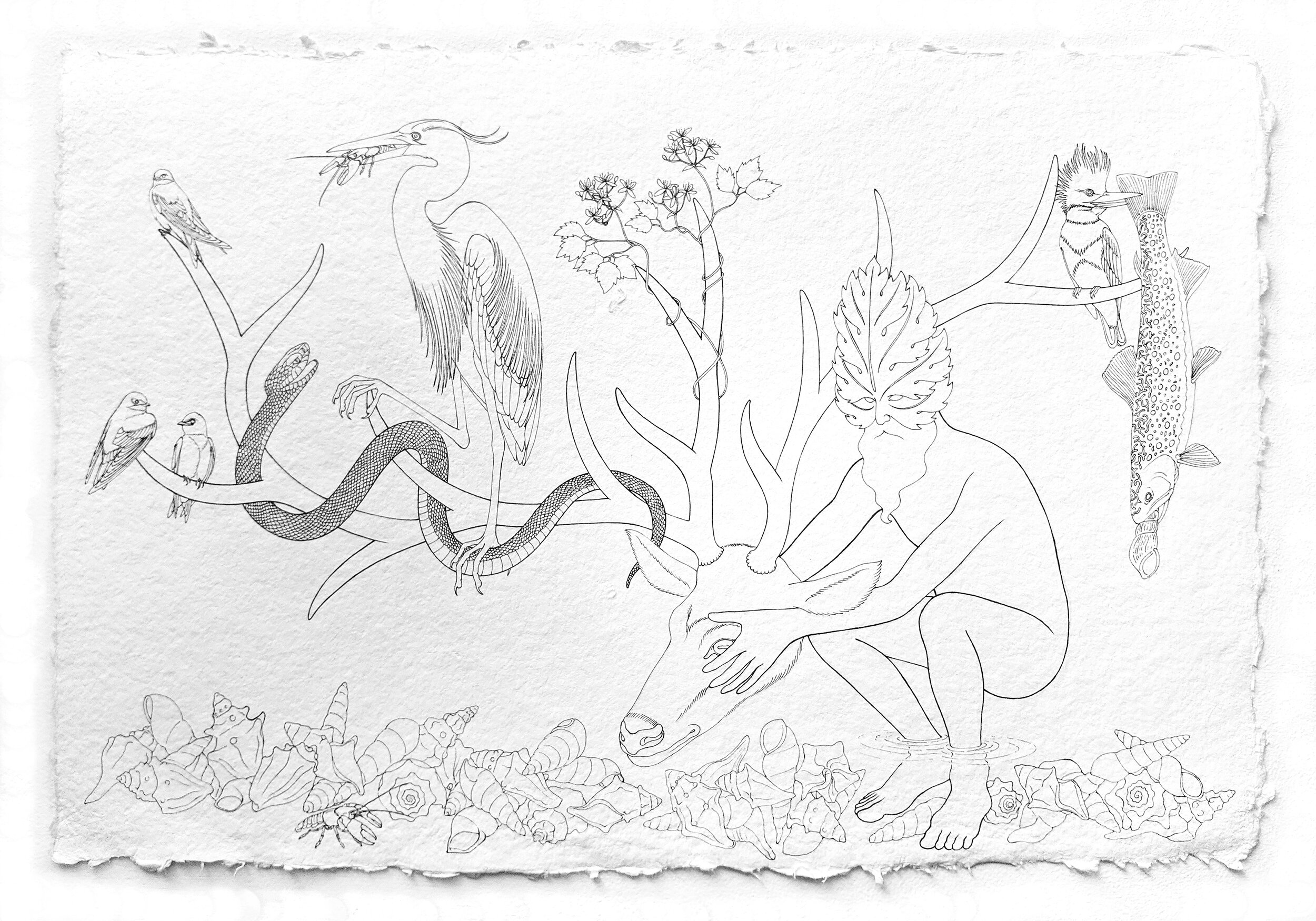

Trevor Foster’s three drawings depict Bosch-like scenes of environmental magic and mysticism. In his vision, he imagines how a post-human world would heal itself after the unavoidable climate-fueled destruction of our planet. A return to Eden led by the spirits and deities from ancient folklore. He imagines how those creatures, such as Green Man and Kodama tree spirits, would renew a burnt and abandoned world, repopulating it with plants and animals. Foster’s clean and confident line mirrors Beardsley’s own formal drawing style, one highly influenced by Japanese prints and print making technological advances of the era. Both artists use carefully observed natural forms and botanical illustrations to illustrate mystical forces of nature. Oscar Wilde said of his story Salomé, which Beardsley illustrated, “my Salomé is a mystic, the sister of Salammbo, a Sainte Thérèse who worships the moon.” Foster’s Green Men worship the same moon, connecting a dystopian future to the Victorian era’s belief in supernatural forces and energies, ectoplasm, spiritualism and wild phenomena.

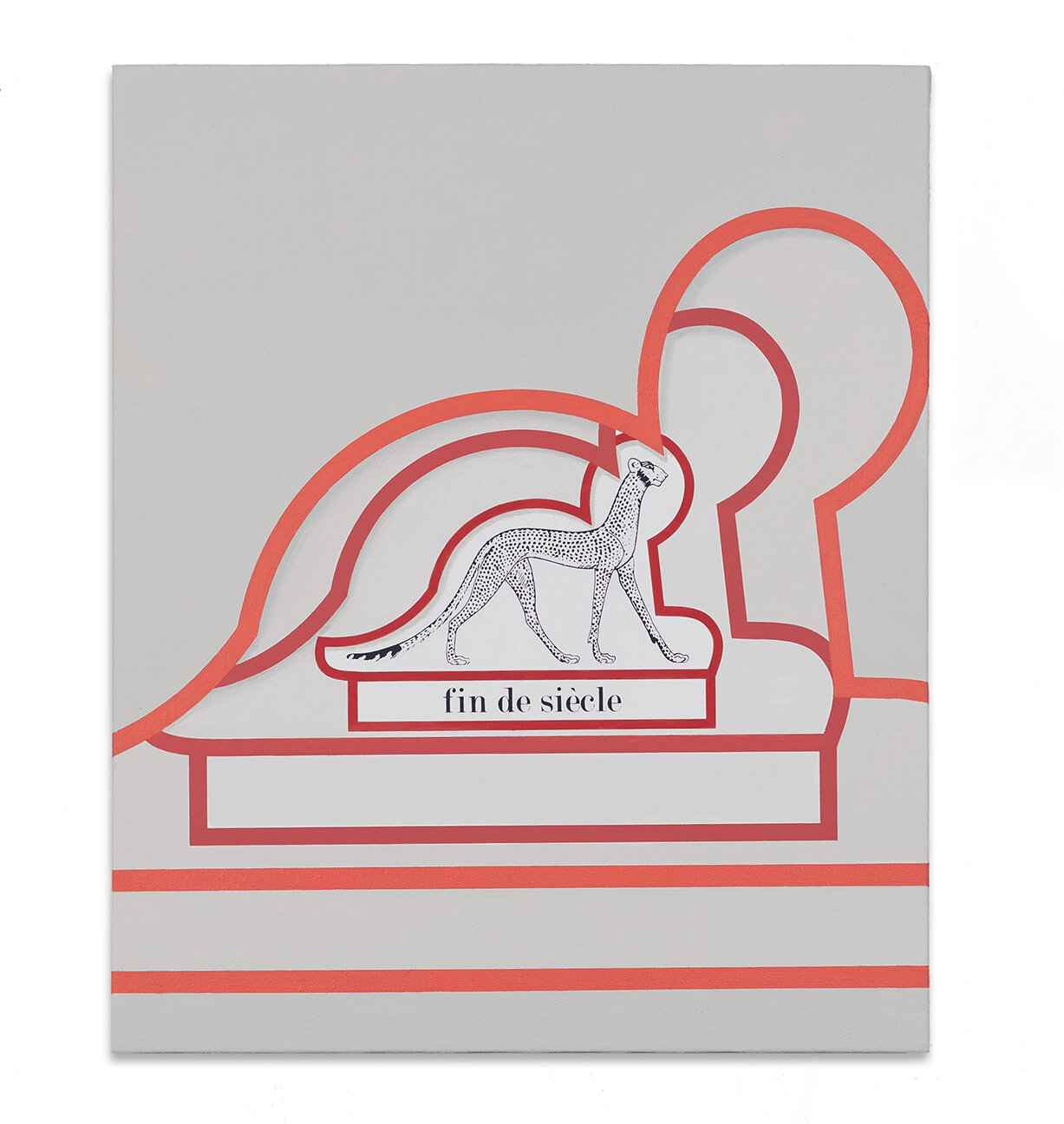

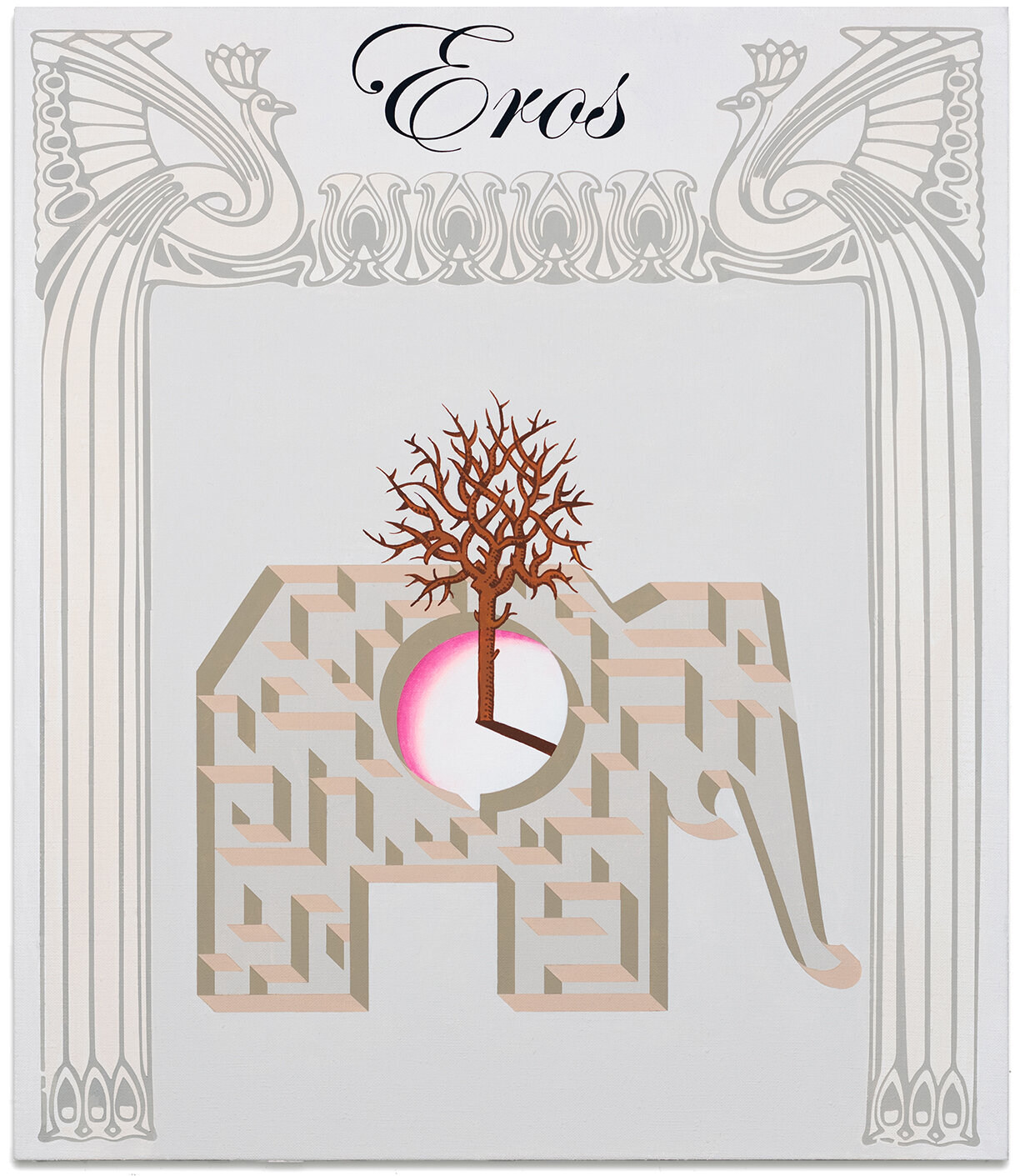

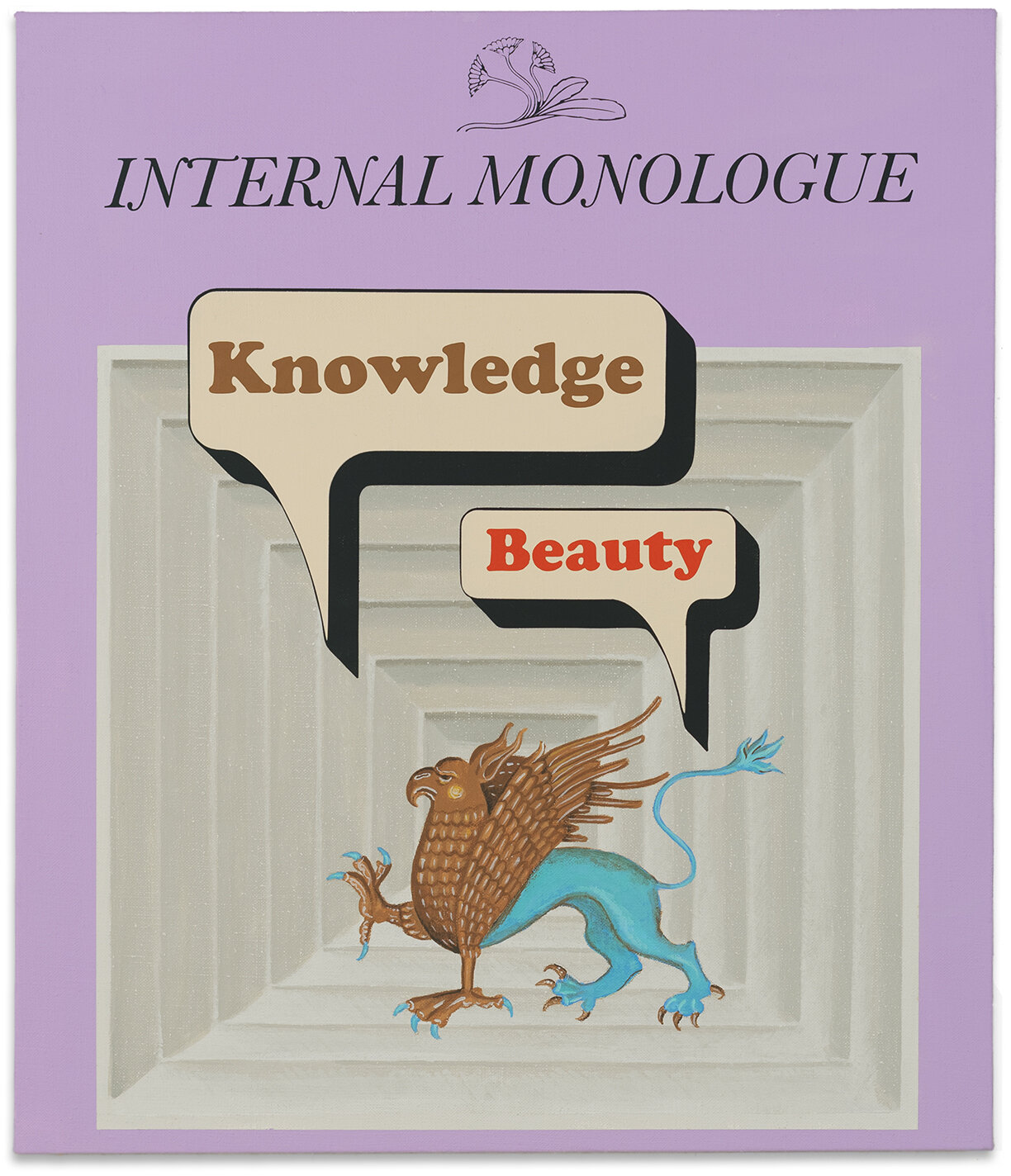

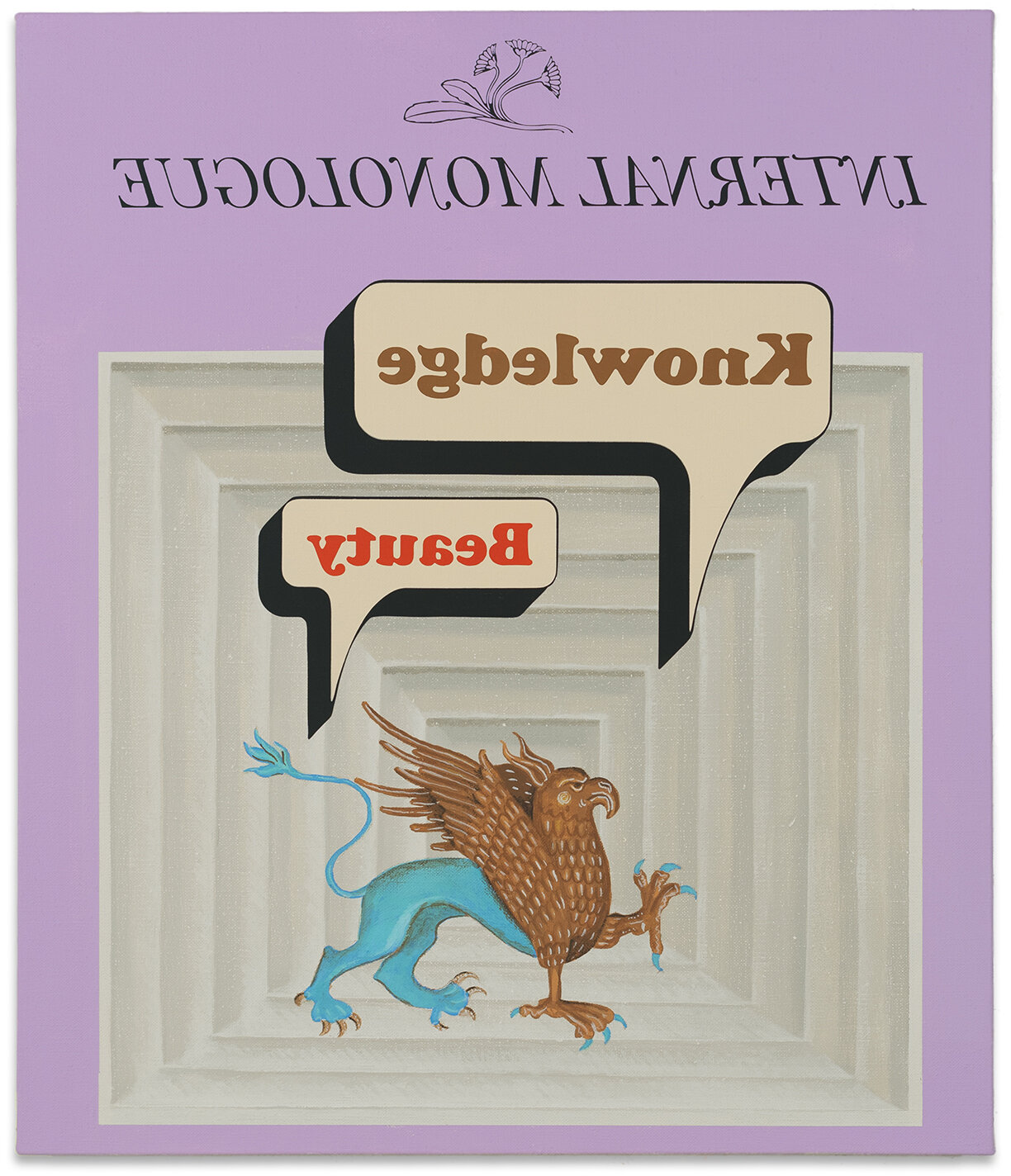

Alan Reid’s three paintings (including one diptych) germinate from the fin de siècle’s embrace of symbolism, or the expression of an idea over the realistic description of the natural world. Traditional themes included love, fear, anguish, death, sexual awakening and unrequited desire but Reid’s paintings, in their powder-room palette of pastels, offer instead deeply encoded references to art history, philosophy, psychology and music. They’re propaganda posters for a mythical past, one full of lost innocence, nostalgia for a gilded simplicity and more fashionable times. Drenched in psychoanalytic humor, puns abound in an aesthetic pulled from antique signage and vintage graphic design. In Reid’s world, painting becomes a physical representation of a psychological state, as in Oscar Wilde’s fin de siècle novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891).

Ryan Flores’ ceramic pieces share genealogies with both fine de siècle and Bodegónes (Spanish still life painting). Differing from the Flemish Baroque still lifes, which often contain both rich banquets, bodegones are austere; the fruits and vegetables are uncooked and the backgrounds are bleak. Flores’s ceramic arrangements contain elements of morbid and macabre with their dripping glaze and disintegrating fruit bodies, but unlike the traditional bodegones which were embedded with moral purpose, Flores does not impose any moral lessons on the audience. Similar to Beardsley’s explorations into the macabre, Flores' fascination is without judgement. His fruits are sculpted and glazed in a way that references still life painting of the early fine de siècle period, such as Antoine Vollon’s Mound of Butter, 1875–85, Paul Cézanne’ s apples or Vincent van Gough’s onions, pears and quinces from the 1880s.

Aubrey Beardsley

Frederick Hollyer’s portrait of Aubrey Beardsley, 1893

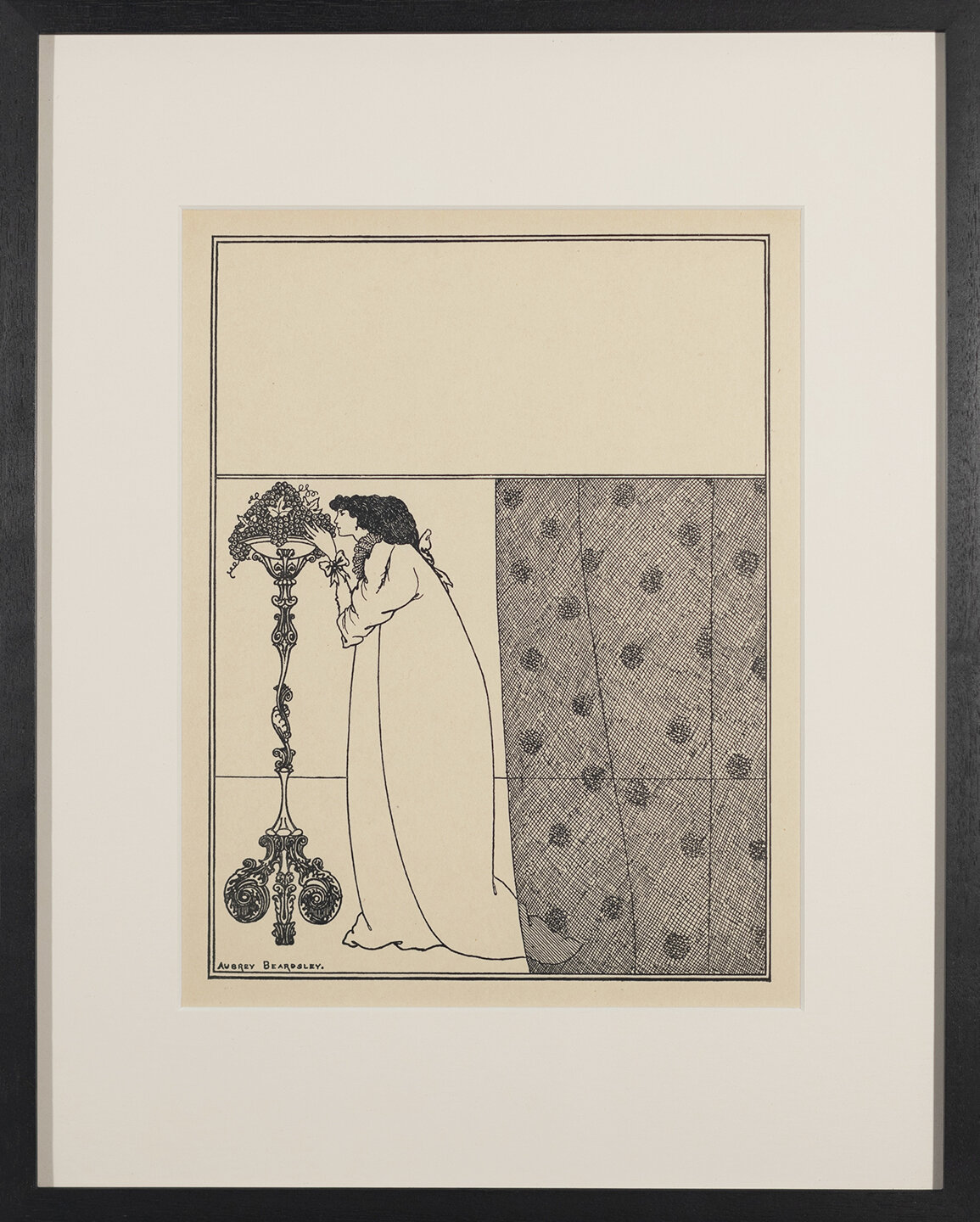

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (1872–1898) was a British illustrator associated with the turn of the century Aesthetic Movement, a group whose members included Oscar Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. Although his short artistic career spanned just under seven years, Beardsley created a breathtaking body of masterful and iconic works that defined Victorian ideas of sexual freedom, gender fluidity and dandyism. Beardsley died in the south of France on March 16th, 1898 from tuberculosis, an illness that plagued him his entire career. He was 25 years old.

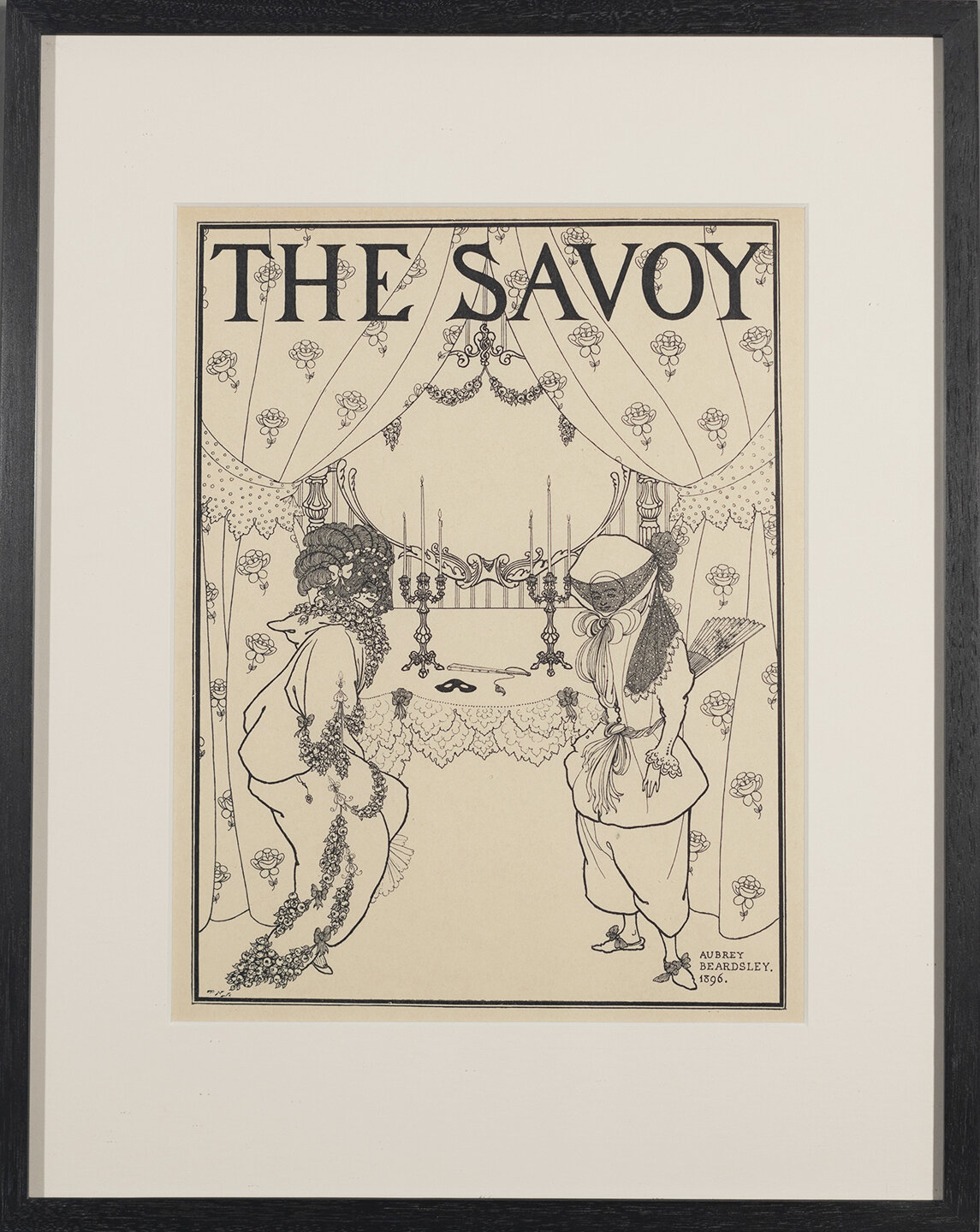

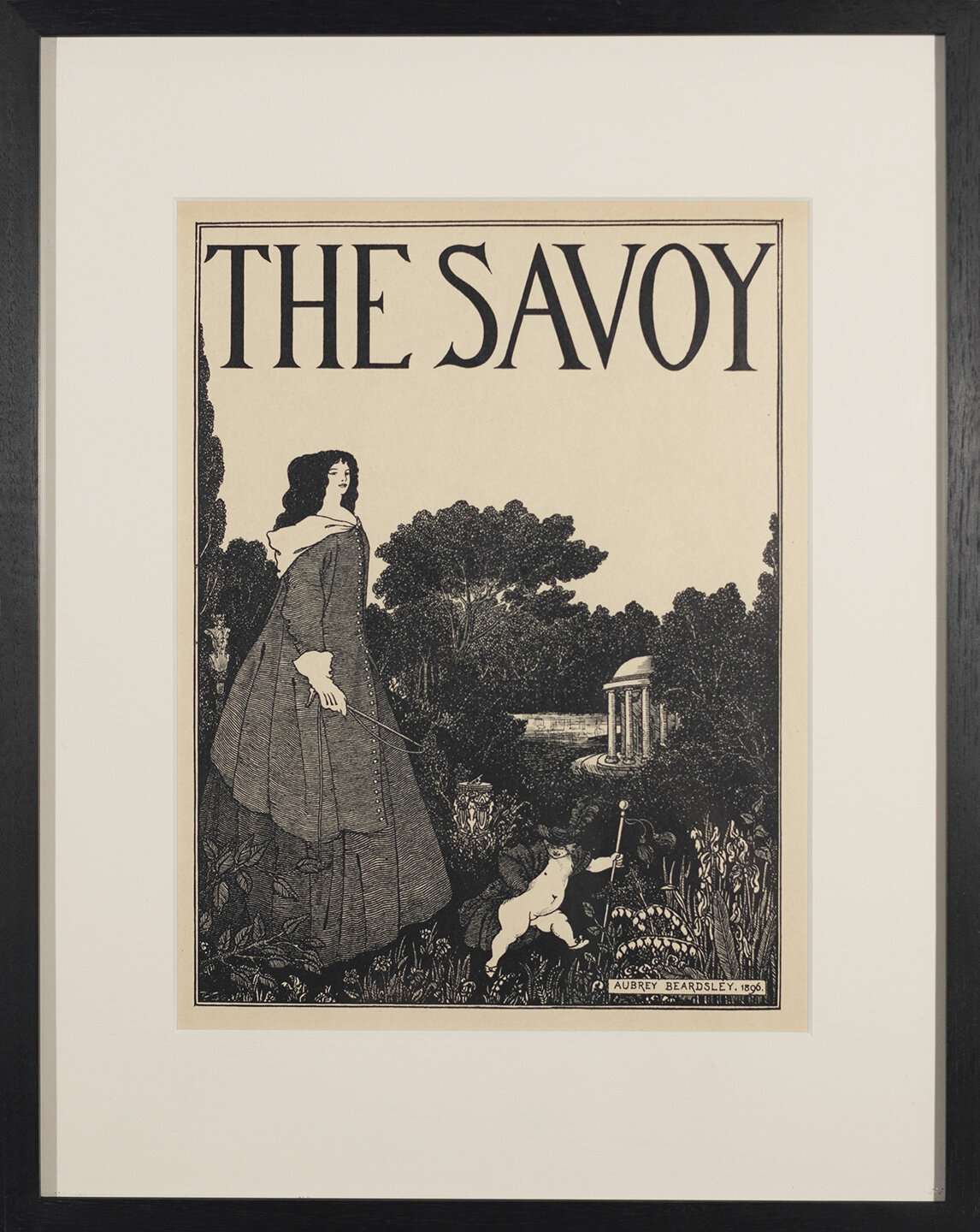

Hailed as one of the more provocative figures from the Art Nouveau era, Beardsley drew his signature style of sweeping thin lines and wide swaths of graphic black from Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e) and in response to a relatively new line block printing process in which drawings are transferred onto printing plates photographically. In 1892, he received his first significant commission to illustrate Le Morte Darthur, Sir Thomas Malory’s version of the legends of King Arthur (J.M. Dent, 1895). This led to the publication of his illustrations in Oscar Wilde’s Salomé (London: Elkin Mathews & John Lane; Boston: Copeland & Day, 1894). That same year, Beardsley became art editor of The Yellow Book, an iconic magazine that published a range of literary and artistic genres, poetry, short stories, essays, and book illustrations bound in a striking yellow and black cover reminiscent of popular french books of the period that contained illicit and scandalous content. In 1985, due to the arrest of Oscar Wilde for indecency, the publisher of The Yellow Book succumbed to public outrage and fired Beardsley for his associations with Wilde.

During a trip to Brussels in the spring of 1896, Beardsley suffered a severe lung hemorrhage, a manifestation of his tuberculosis, from which he never fully recovered. In search of cleaner air, Beardsley moved to Dieppe, France and was invited by the publisher (and occasional pornographer) Leonard Smithers to launch a new magazine titled The Savoy . With Beardsley as art editor and the poet Arthur Symons in charge of literature, the fledgling publication sadly folded after a year - but not before leaving an indelible mark on the times. As his health continued to deteriorate, Beardsley went on to illustrate the 1896 publication of Alexander Pope’s epic poem The Rape of the Lock (1712) and Théophile Gautier’s novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) for Leonard Smithers. In 1897 he tackled elaborate and controversial aspects of sexuality by illustrating the Greek comedy, Lysistrata, by Aristophanes and Latin author Juvenal’s Sixth Satire. Beardsley, a recent convert to Catholicism, asked Leonard Smithers from his death bed to “…destroy all copies of Lysistrata and bad drawings … By all that is holy, all obscene drawings.” Smithers ignored the request and published these last two projects through private subscription.

Two major exhibitions have been curated on Beardsley’s work: “Aubrey Beardsley,” at the Tate Britain, Mar. 4th–Sept. 20th, 2020 and “Aubrey Beardsley,” at the Victoria and Albert Museum, May 19th–Sept. 19th, 1966.

His work continues to have far reaching influences; from a surge of popularity among young avant-garde Russians before WW1 to an adaptation by sixties graphic and fashion designers.